Pub history

The Friar Penketh

Discover the history of Warrington.

This pub stands on the site of a 13th-century Augustinian friary. One of the friars, a scholar called Friar Penketh, is mentioned in Shakespeare’s King Richard III. Today, the street names of Friars Gate and St Augustin’s Lane are reminders of the religious house which once stood here.

An illustration, print and text about the market and Market Gate

The text reads: In 1255, Warrington was granted the single most important factor in its early development – a market. Further charters were obtained in 1277 and 1285. Market Gate dates from at least 1363.

Top: Warrington Market in 1834

Above: The first electric tram at Market Gate. Work on the tramways began in 1901. They were not completely replaced by motor buses until 1935

Right: Market Gate and motor vehicles in 1928

Photographs and text about Sunlight Soap

The text reads: William Hesketh Lever started out in his father’s grocery business in Bolton when he was 16. A partner at 21, he was a wealthy man in his early thirties. It was then that he decided to go into the soap business. His first move was to think up a name. After several days, inspiration struck when Sunlight came into his mind. He leased Winser’s chemical works here in Warrington (top, left) which was already making soap in 1885, but no money, and produced his first experimental boil of Sunlight soap in 1885, a recipe that changed little in the coming years. He was overwhelmed with orders. Needing to expand, he found a site in Cheshire and named it Port Sunlight (left). The future was to bring Lifebouy Soap, the first soap flakes, later called Lux, and the development of Vim. Mergers added Persil to Lever’s brands and led to the new name Unilever in 1929. His title, 1st Viscount Leverhulme, combined his own and his wife’s family names.

Right: Lever with his wife and son

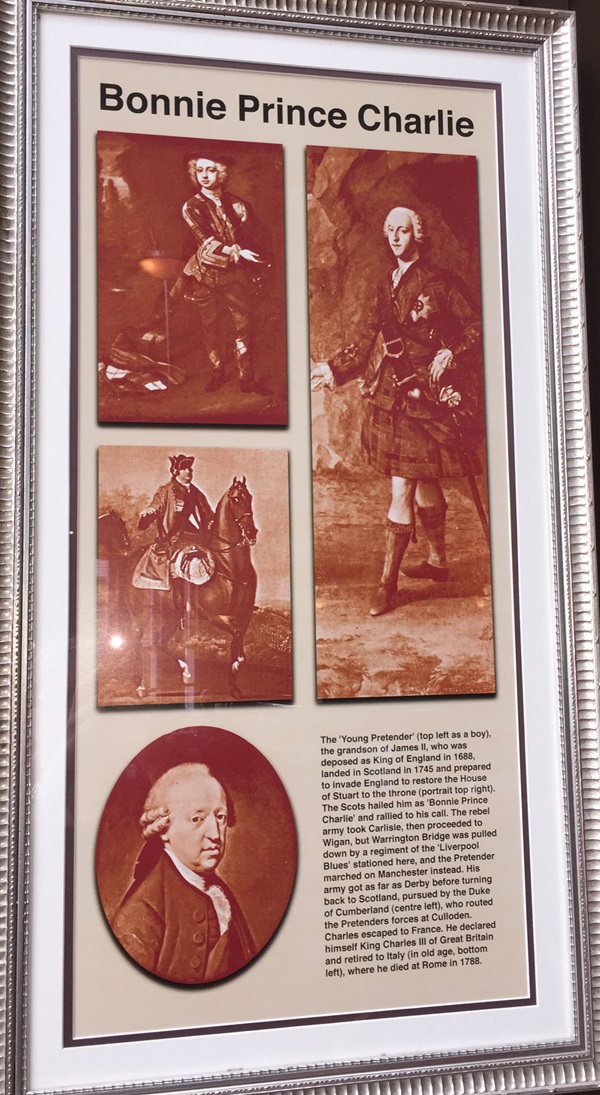

Prints and text about ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’

The text reads: The ‘Young Pretender’ (top left as a boy), the grandson of James II, who was deposed as King of England in 1688, landed in Scotland in 1745 and prepared to invade England to restore the House of Stuart to the throne (portrait top right). The Scots hailed him as ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ and rallied to his call. The rebel army took Carlisle, then proceeded to Wigan, but Warrington Bridge was pulled down by a regiment of the ‘Liverpool Blues’ stationed here, and the Pretender marched on Manchester instead. His army got as far as Derby before turning back to Scotland, pursued by the Duke of Cumberland, who routed the Pretender’s forces at Culloden. Charles escaped to France. He declared himself King Charles III of Great Britain and retired to Italy (in old age, bottom left), where he died at Rome in 1788.

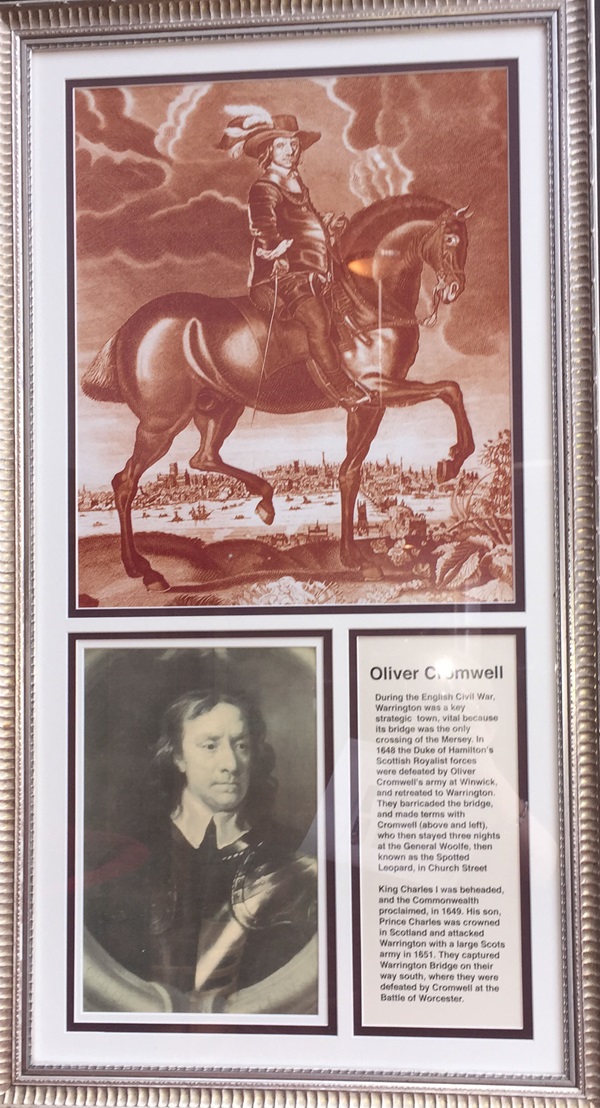

An illustration, print and text about Oliver Cromwell

The text reads: During the English Civil War, Warrington was a key strategic town, vital because its bridge was the only crossing of the Mersey. In 1648, the Duke of Hamilton’s Scottish Royalist forces were defeated by Oliver Cromwell’s army at Winwick, and retreated to Warrington. They barricaded the bridge and made terms with Cromwell (above and left), who then stayed three nights at the General Woolfe, then known as the Spotted Leopard, in Church Street.

King Charles I was beheaded, and the Commonwealth proclaimed, in 1649. His son, Prince Charles, was crowned in Scotland and attacked Warrington with a large Scots army in 1651. They captured Warrington Bridge on their way south, where they were defeated by Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester.

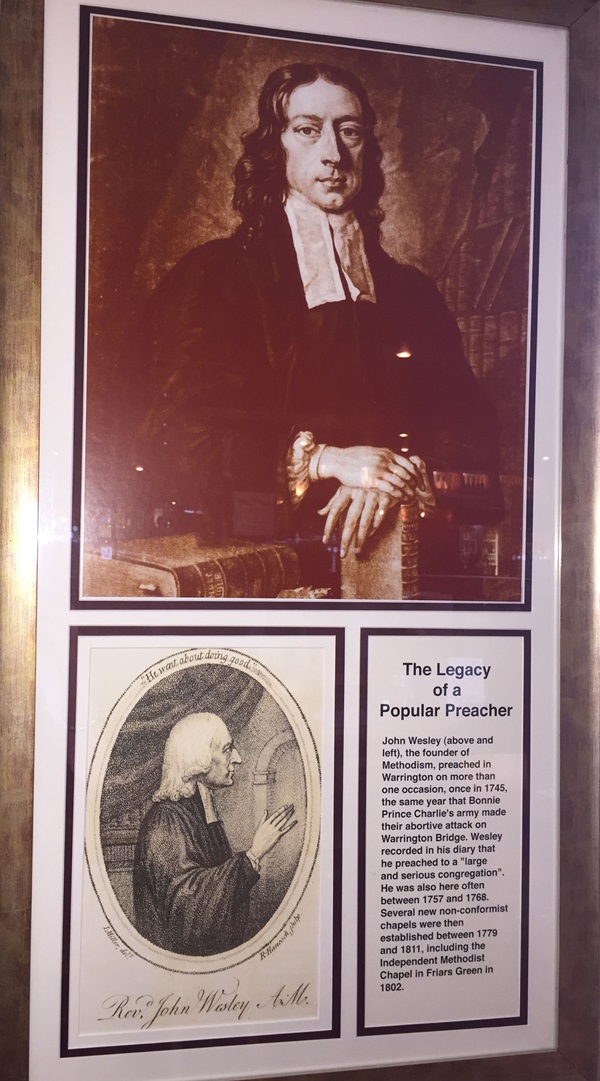

A print, illustration and text about John Wesley

The text reads: John Wesley (above and left), the founder of Methodism, preached in Warrington on more than one occasion, once in 1745, the same year that Bonnie Prince Charlie’s army made their abortive attack on Warrington Bridge. Wesley recorded in his diary that he preached to a ‘large and serious congregation’. He was also here often between 1757 and 1768. Several new non-conformist chapels were then established between 1779 and 1811, including the Independent Methodist Chapel in Friars Green in 1802.

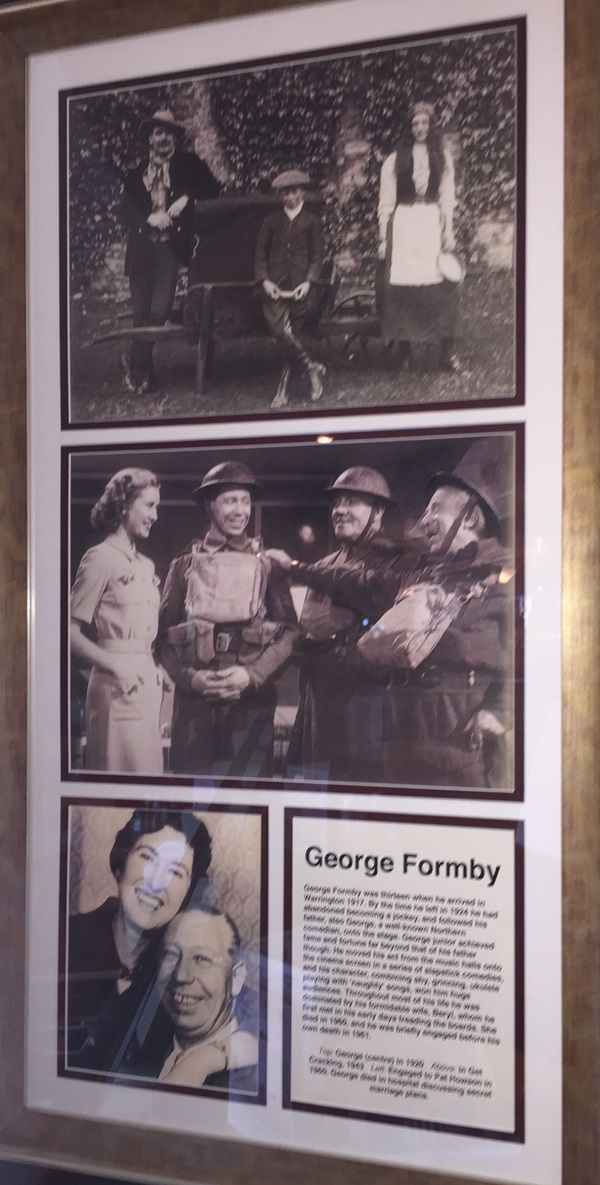

Photographs and text about George Formby

The text reads: George Formby was 13 when he arrived in Warrington in 1917. By the time he left in 1924, he had abandoned becoming a jockey, and followed his father, also George, a well-known Northern comedian, onto the stage. George junior achieved fame and fortune far beyond that of his father though. He moved his act from the music halls onto the cinema screen in a series of slapstick comedies, and his character, combining shy, grinning, ukulele playing with ‘naughty’ songs, won him huge audiences. Throughout most of his life, he was dominated by his formidable wife, Beryl, whom he first met in his early days treading the boards. She died in 1960, and he was briefly engaged before his own death 1961.

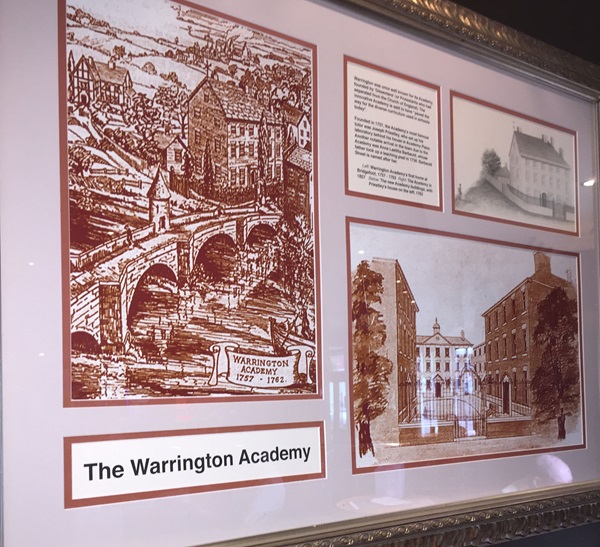

Illustrations and text about the Warrington Academy

The text reads: Warrington was once well known for its academy, founded by ‘Dissenters’ (or Protestants who had separated from the Church of England). The innovative academy is said to have ‘paved the way for the diverse curriculum used in schools today’.

Founded in 1757, the academy’s most famous tutor was Joseph Priestley, who set up his laboratory behind his house in Academy Place. Another notable arrival in the town due to the academy was Anna Laetitia Barbauld, whose father took up a teaching post in 1758. Barbauld Street is named after her.

Left: Warrington Academy’s first home at Bridgefoot, 1757–62

Right: The academy in 1857

Below: The new academy buildings, with Priestley’s house on the left (1762)

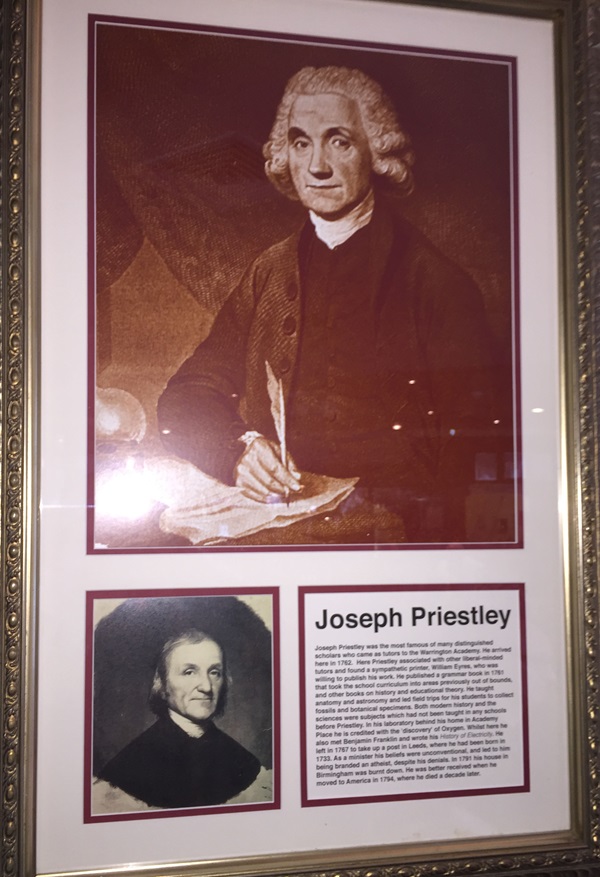

Prints and text about Joseph Priestley

This text read: Joseph Priestley was the most famous of many distinguished scholars who came as tutors to the Warrington Academy. He arrived here in 1762. Here, Priestley associated with other liberal-minded tutors and found a sympathetic printer, William Eyres, who was willing to publish his work. He published a grammar book in 1761 that took the school curriculum into areas previously out of bounds, and other books on history and educational theory. He taught anatomy and astronomy and led field trips for his students to collect fossils and botanical specimens. Both modern history and the sciences were subjects which had not been taught in any schools before Priestley. In his laboratory behind his home in Academy Place, he is credited with the ‘discovery’ of oxygen. Whilst here, he also met Benjamin Franklin and wrote History of Electricity. He left in 1767 to take up a post in Leeds, where he had been born in 1733. As a minister, his beliefs were unconventional and led to him being branded an atheist, despite his denials. In 1791, his house in Birmingham was burnt down. He was better received when he moved to America in 1794, where he died a decade later.

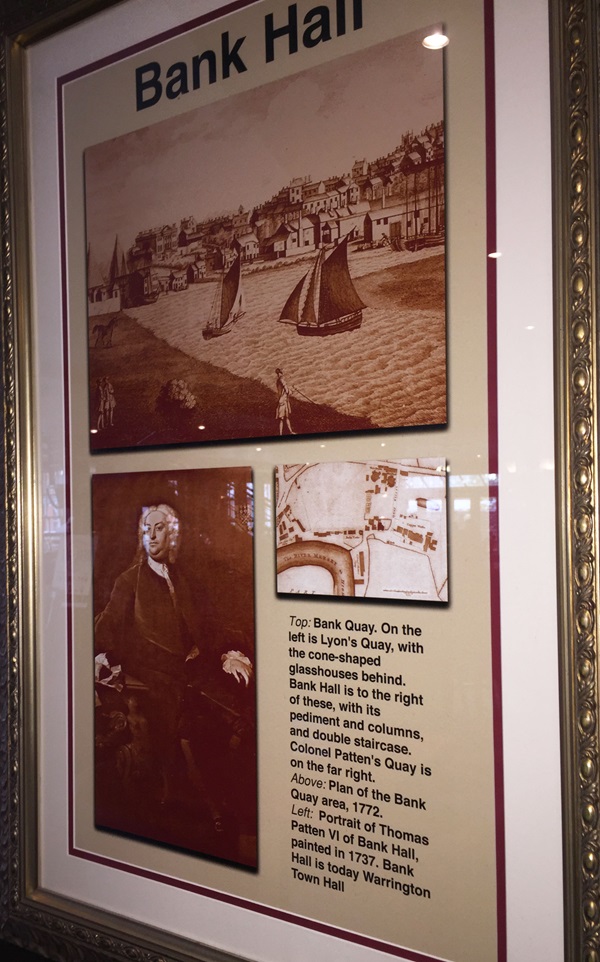

Illustrations and text about Bank Quay

Top: Bank Quay. On the left is Lyon’s Quay, with the cone-shaped glasshouses behind. Bank Hall is to the right of these, with its pediment and columns, and double staircase. Colonel Patten’s Quay is on the far right.

Above: Plan of the Bank Quay area, 1772.

Left: Portrait of Thomas Patten VI of Bank Hall, painted in 1737. Bank Hall is today Warrington Town Hall.

Photographs and text about Bridge Street

Top: A photograph of Bridge Street in 1887 looking down towards Bridgefoot. This picture was taken from the near Friars Gate, before all the buildings on the west side of the street were demolished to allow for road-widening.

Above: Bridge Street, near Friars Gate. Ten years later than the image above, and looking in the opposite direction.

External photograph of the building – main entrance