Pub history

The Wye Bridge House

Before the arrival of the railway, this site was a private residence – Wye Bridge House (the River Wye runs nearby). In 1921, the premises were purchased by Buxton Corporation, which then began to develop Ashwood Park and Café. More recently, these premises became a public house, keeping the name Ashwood Park Hotel.

Before the arrival of the railway, this site was a private residence – Wye Bridge House (the River Wye runs nearby). In 1921, the premises were purchased by Buxton Corporation, which then began to develop Ashwood Park and Café. More recently, these premises became a public house, keeping the name Ashwood Park Hotel.

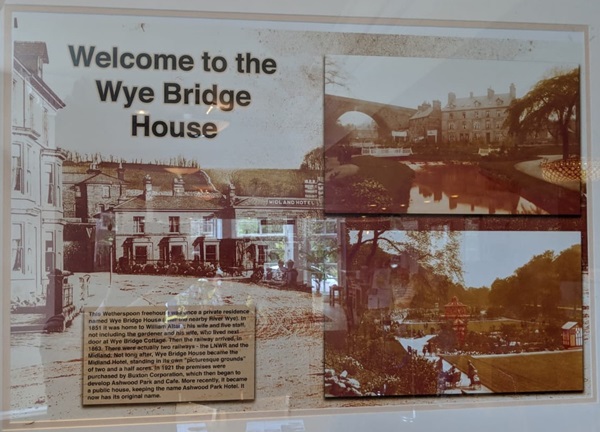

Photographs and text about The Wye Bridge House

The text reads: This Wetherspoon free house was once a private residence named Wye Bridge House (after the nearby River Wye). In 1851, it was home to William Altare, his wife and five staff, not including the gardener and his wife, who lived next door at Wye Bridge Cottage. Then the railway arrived, in 1863. There were actually two railways – the LNWR and the Midland. Not long after, Wye Bridge House became the Midland Hotel, standing in its own ‘picturesque grounds’ of two and a half acres. In 1921, the premises were purchased by Buxton Corporation, which then began to develop Ashwood Park and Café. More recently, it became a public house, keeping the name Ashwood Park Hotel. It now has its original name.

A print and text about Wye Bridge House

The text reads: This J D Wetherspoon pub was originally a private residence named Wye Bridge House. In 1851, it was home to William Altare, his wife Elizabeth and their five servants. Their gardener and his wife lived in nearby Wye Bridge Cottage. Ten years later, the house was occupied by a Mrs Fawdington and her daughter.

After the railways arrived in Buxton, new hotels were opened to accommodate the huge number of visitors.

Photographs and text about Vera Brittain

The text reads: Born in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Vera came to Buxton with her parents at the age of 11. Her father, a wealthy paper-manufacturer, called Buxton “a little box of social strife lying at the bottom of a basin”.

Vera later became a writer of fiction and poetry. However, she is best remembered for two volumes of autobiography, Testament of Youth and Testament of Experience.

Of the first, dealing with the First World War period, Brittain’s friend and fellow-author Winifred Holtby wrote: ‘no-one has yet so convincingly conveyed its grief.’ Testament of Friendship, published in 1940, was Brittain’s biography of Holtby, who died at 37. Holtby’s best-known work is the novel South Riding.

Vera Brittain’s daughter is the former Labour and now Liberal Democrat politician, Shirley Williams.

Top, left: Vera’s family in a car

Top, right: Vera nursing in Malta

Above: Vera and her two children, c1934

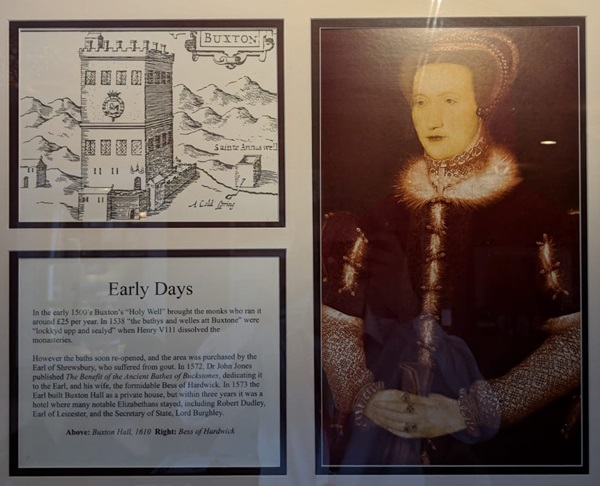

Prints and text about the early days of Buxton

The text reads: In the early 1500s, Buxton’s ‘Holy Well’ brought the monks who ran it around £25 per year. In 1538, ‘the bathys and welles att Buxtone’ were ‘lockkyd upp and sealyd’ when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries.

However, the baths soon re-opened, and the area was purchased by the Earl of Shrewsbury, who suffered from gout. In 1572, Dr John Jones published The Benefit of the Ancient Bathes of Buckstones, dedicating it to the Earl, and his wife, the formidable Bess of Hardwick. In 1573, the Earl built Buxton Hall as a private house, but within three years it was a hotel where many notable Elizabethans stayed, including Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and the Secretary of State, Lord Burghley.

Above: Buxton Hall, 1610

Right: Bess of Hardwick

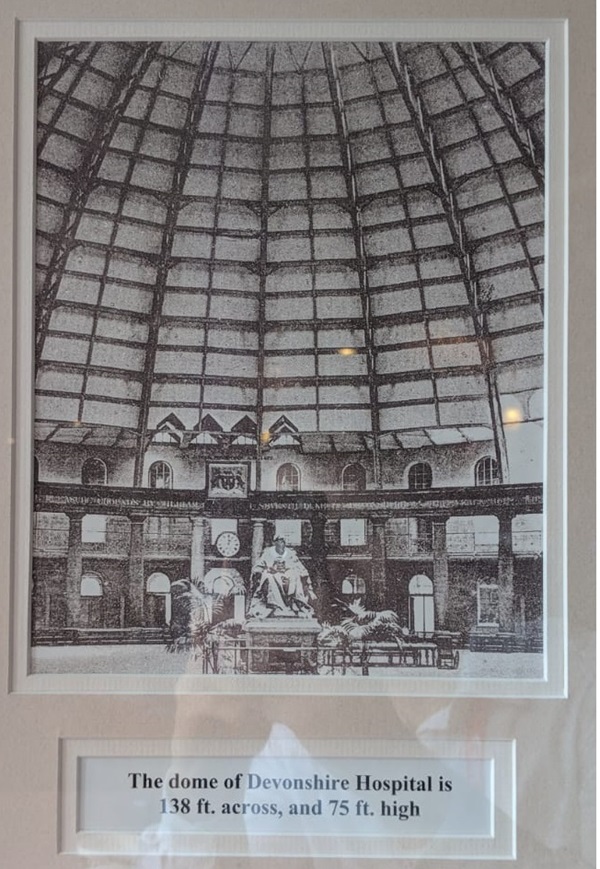

A print of the dome of Devonshire Hospital – it is 138 feet across, and 75 feet high

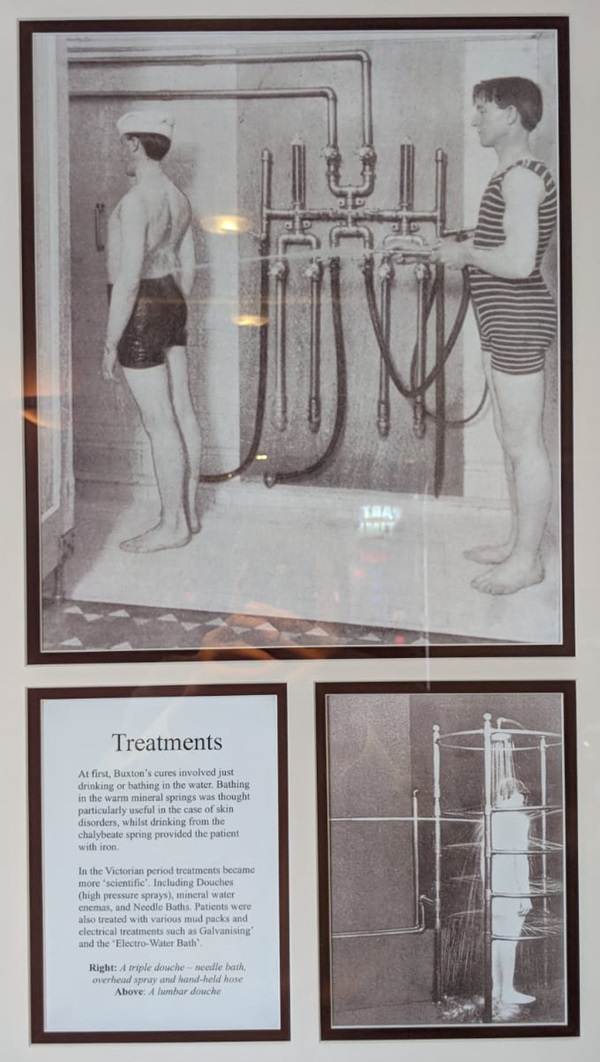

Photographs and text about treatments in Buxton

The text reads: At first, Buxton’s cures involved just drinking or bathing in the water. Bathing in the warm mineral springs was thought particularly useful in the case of skin disorders, whilst drinking from the chalybeate spring provided the patient with iron.

In the Victorian period, treatments became more ‘scientific’. Including douches (high pressure sprays), mineral water enemas, and Needle Bath. Patients were also treated with various mud packs and electrical treatments and such as ‘galvanising’ and the ‘Electro-Water Bath’.

Right: A triple douche – needle bath, overhead spray and hand-held house

Above: A lumbar douche

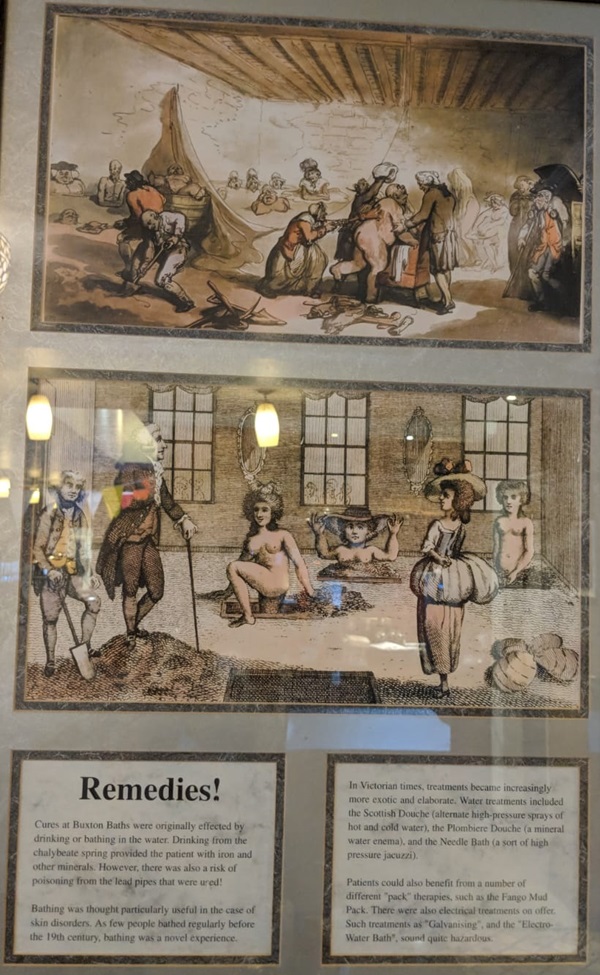

Illustrations and text about cures at Buxton Baths

The text reads: Cures at Buxton Baths were originally effected by drinking or bathing in the water. Drinking from the chalybeate spring provided the patient with iron and other minerals. However, there was also a risk of poisoning from the lead pipes that were used!

Bathing was thought particularly useful in the case of skin disorders. As few people bathed regularly before the 19th century, bathing was a novel experience.

In Victorian times, treatments became increasingly exotic and elaborate. Water treatments included the Scottish Douche (alternate high-pressure sprays of hot and cold water), the Plombiere Douche (a mineral water enema), and the Needle Bath (a sort of high-pressure Jacuzzi).

Patients could also benefit from a number of different ‘pack’ therapies, such as the Fango Mud Pack. There were also electrical treatments on offer. Such treatments as ‘galvanising’ and the ‘Electro-Water Bath’ sound quite hazardous.

Old illustrations of Buxton

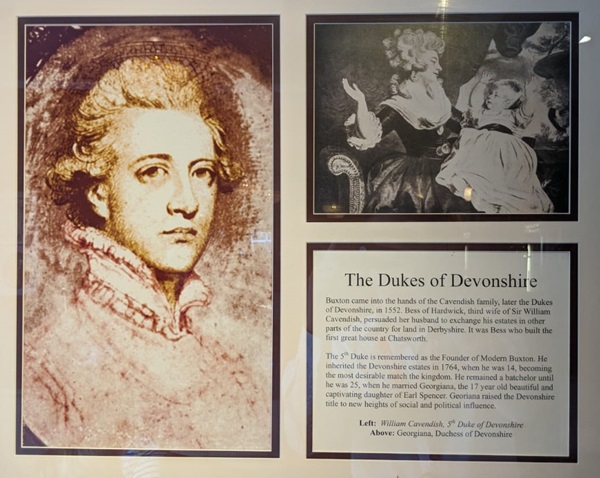

Prints and text about the Dukes of Devonshire

The text reads: Buxton came into the hands of the Cavendish family, later the Dukes of Devonshire, in 1552. Bess of Hardwick, third wife of Sir William Cavendish, persuaded her husband to exchange his estates in other parts of the country for land in Derbyshire. It was Bess who built the first great house at Chatsworth.

The fifth Duke is remembered as the founder of modern Buxton. He inherited the Devonshire estates in 1764, when he was 14, becoming the most desirable match in the kingdom. He remained a bachelor until he was 25, when he married Georgiana, the 17-year-old beautiful and captivating daughter of Earl Spencer. Georgiana raised the Devonshire title to new heights of social and political influence.

Left: William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire

Above: Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

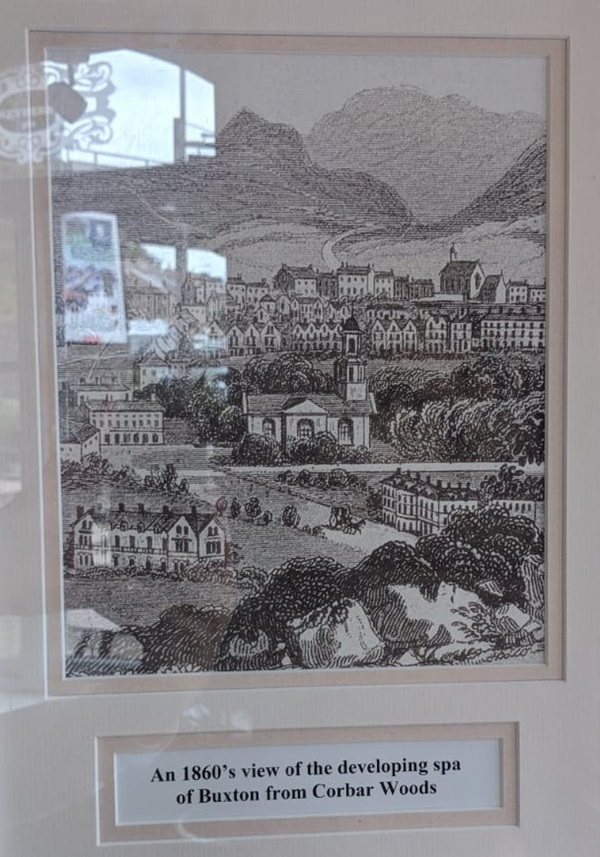

An illustration of an 1860s view of the developing spa of Buxton from Corbar Woods

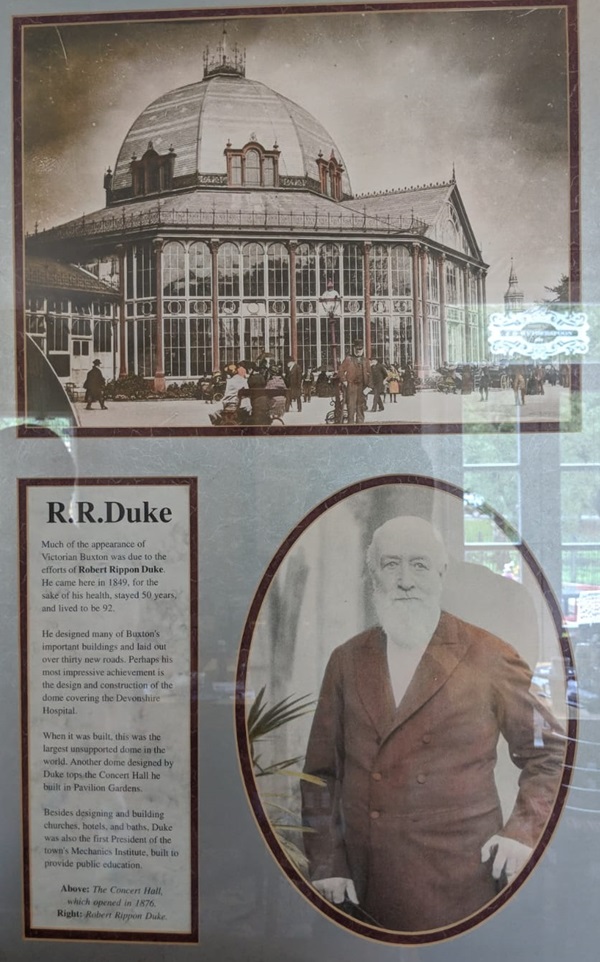

Prints and text about RR Duke

The text reads: Much of the appearance of Victorian Buxton was due to the efforts of Robert Rippon Duke. He came here in 1849, for the sake of his health, stayed 50 years, and lived to be 92.

He designed many of Buxton’s important buildings and laid out over 30 new roads. Perhaps his most impressive achievement is the design and construction of the dome covering the Devonshire Hospital.

When it was built, this was the largest unsupported dome in the world. Another dome designed by Duke tops the Concert Hall he built in Pavilion Gardens.

Besides designing and building churches, hotels, and baths, Duke was also the first president of the town’s Mechanics Institute, built to provide public education.

Above: The Concert Hall, which opened in 1876

Right: Robert Rippon Duke.

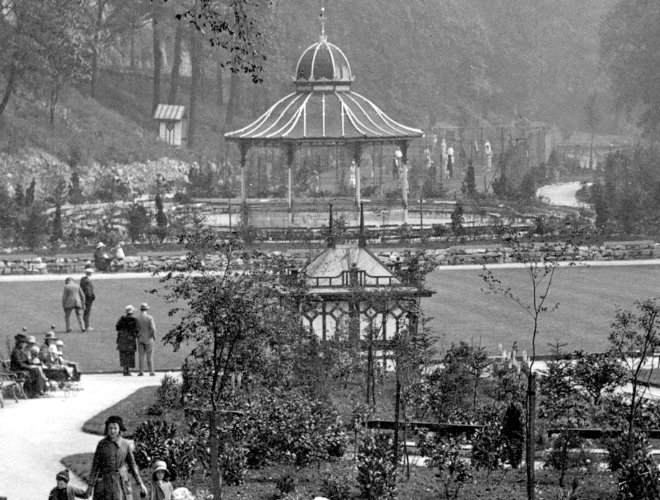

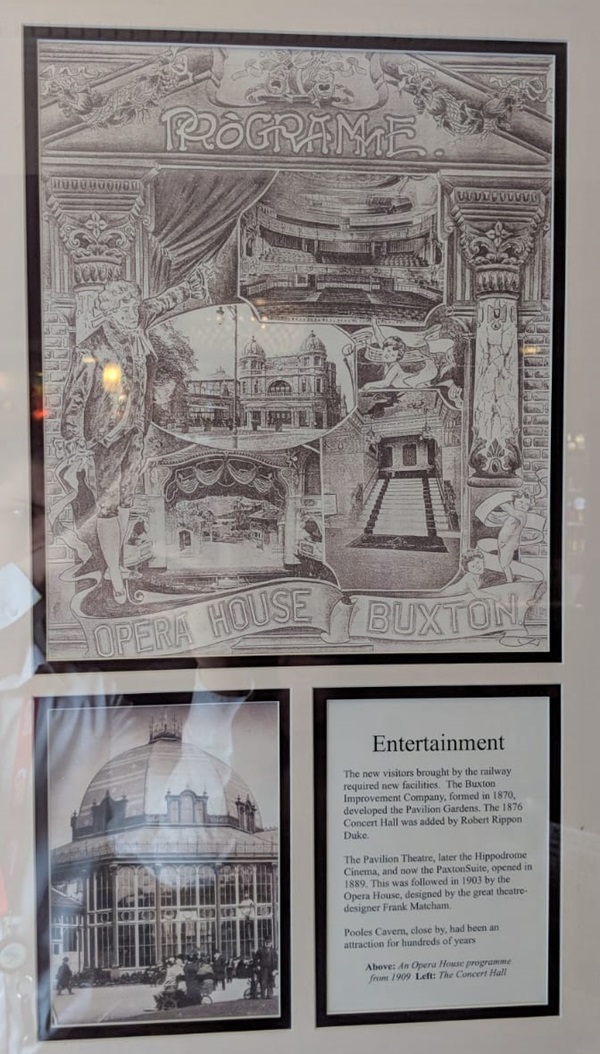

Prints and text about entertainment in Buxton

The text reads: The new visitors brought by the railway required new facilities. The Buxton Improvement Company, formed in 1870, developed the Pavilion Gardens. The 1876, Concert Hall was added by Robert Rippon Duke.

The Pavilion Theatre, later the Hippodrome Cinema and now the Paxton Suite, opened in 1889. This was followed in 1903 by the Opera House, designed by the great theatre-designer Frank Matcham.

Pooles Cavern, close by, had been an attraction for hundreds of years.

Above: An Opera House programme from 1909

Left: The Concert Hall

External photograph of the building – main entrance