Pub history

The Beehive

With shopping well established here by the early 19th century, Brixton has long been famous for its shops and markets. In 1824, there were also seven pubs and six boot and shoemakers. In 1909, a shoe shop opened in these premises. Truform’s eventually closed in 1993 and became The Beehive. The pub takes its name from Beehive Place, at the rear, which was originally known as Back Lane and was built to serve those properties fronting onto Brixton Road.

407–409 Brixton Road, Brixton, London, SW9 7DG

This pub was a long-standing shoe shop which first opened in 1909, taking its name from Beehive Place to the rear of these premises.

Framed photographs and text about Herbert Morrison.

The text reads: A brilliant and intuitive politician, Herbert Morrison, the youngest child of a policeman with a weakness for the bottle, rose to become Deputy Prime Minister in the post-war Labour Government and Deputy Leader of the Labour Party.

Herbert Stanley Morrison was born at 240 Ferndale Road, Brixton, in 1888. His family shared the house with its owner, a milkman who kept his horse and cart in sheds at the bottom of the garden. A few years later, as a reward for their services in building up the milkround, they were given 39 Mordaunt Street – on condition that it was to be inherited by Herbert.

In his autobiography, Morrison looked back on his unloved schooldays at Stockwell Road Board School: “That school of mine – I can see it, feel it, smell it now. Dark paint, heavy walls, a feeling that the roof was falling in on you”.

Beating was common. After being appointed stair monitor, Bert slid down the banisters and was caught. He received six strokes of the cane and was deprived of his first position of responsibility.

He left school at the age of fourteen and after spells as a shop assistant, switchboard, operator, and dabbling in journalism, he worked as circulation manager for the Daily Citizen, the first official Labour paper. In April 1915, Morrison was appointed as the part-time secretary of the London Labour Party and from then on politics was his living, either as an organizer or Member of Parliament.

It was in those early years, after leaving school, that Morrison first seriously started reading books. One Friday night in Rushcroft Road, outside the Tate Library, he listed to a speaker on Phrenology (or the ‘reading’ of heads), which was then considered a respectable science.

In Morrison’s own words, “He gave me the best advice I ever had”. Until then, Herbert’s reading had been limited to the exploits of characters such as ‘Deadwood Dick’ and ‘Mysterious Gutch’. For the first time he was encouraged to reach out for “better stuff”. Books became a passion and his reading drove him to socialism.

There was no sudden revelation but a gradual intellectual conversion, leading to Morrison’s lifelong pre-occupation with the issues of transport, health, education and the provision of housing by local authorities.

Morrison’s greatest achievements in politics were probably in the inter-war years. He served in Ramsay MacDonald’s minority Labour Government and, in particular, he dominated the London County Council which introduced many reforms, including slum clearances and school building.

Possibly the climax of Morrison’s career was the Labour landslide general election victory, in 1945. He had played a considerable part in its making – managing the Party machine, which channelled post-war expectations into the ballot box, and as one of a small group of Labour leaders who successfully held high office through the war years showing that such men could rule effectively.

Many of Morrison’s highest offices and achievements followed the 1945 victory yet there were also disappointments. Although he denied seeking the post of Prime Minister for himself, there was high-level support for him to seek the top job. He also pressed his own case for several days after Atlee was designated Prime Minister. After Labour left office Atlee held onto the leadership until age effectively ruled Morrison out as his successor.

Herbert Morrison was an unusual type of Labour leader. He did not make his way through the trade union movement nor was he part of the middle class intellectual grouping, prominent in senior party ranks.

After his death in 1965, his ashes were scattered in London, on the River Thames.

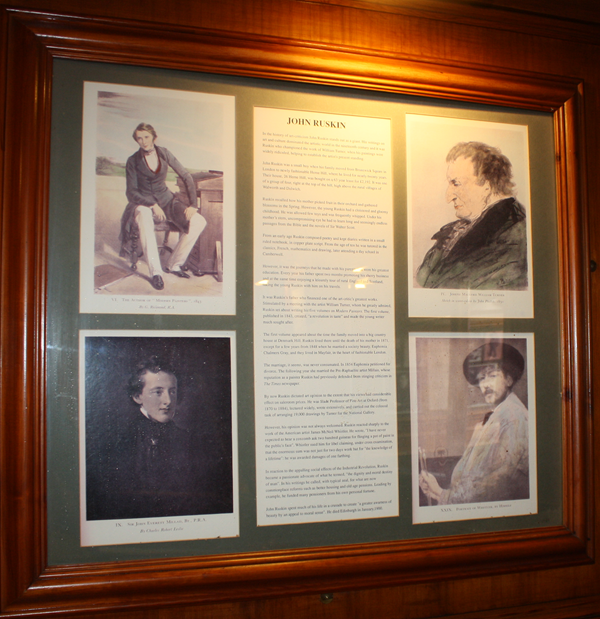

Framed photographs, drawings and text about John Ruskin.

The text reads: In the history of art-criticism John Ruskin stands out as a giant. His writings on art and culture dominated the artistic world in the nineteenth century and it was Ruskin who championed the work of William Turner, when his paintings were widely ridiculed, helping to establish the artist’s present standing.

John Ruskin was a small boy when his family moved from Brunswick Square in London to newly fashionable Herne Hill, where he lived for nearly twenty years. Their house, 26 Herne Hill, was bought on a 63 year lease for £2,192. It was one of a group of four, right at the top of the hill, high above the rural villages of Walworth and Dulwich.

Ruskin recalled how his mother picked fruit in their orchard and gathered blossoms in the Spring. However, the young Ruskin had a cloistered and gloomy childhood. He was allowed few toys and was frequently whipped. Under his mother’s stern, uncompromising eye he had to learn long and seemingly endless passages from the Bible and the novels of Sir Walter Scott.

From an early age Ruskin composed poetry and kept diaries written in a small ruled notebook, in copper plate script. From the age of ten he was tutored in the classics, French, mathematics and drawing, later attending a day school in Camberwell.

However, it was the journeys that he made with his parents that were his greatest education. Every year his father spent two months promoting his sherry business and at the same time enjoying a leisurely tour of rural England and Scotland taking the young Ruskin with him on his travels.

It was Ruskin’s father who financed one of the art-critic’s greatest works. Stimulated by a meeting with the artist William Turner, whom he greatly admired, Ruskin set about writing his five volumes on Modern Painters. The first volume published in 1843, created, “a revolution in taste” and made the young writer much sought after.

The first volume appeared about the time the family moved into a big country house at Denmark Hill. Ruskin lived there until the death of his mother in 1871, except for a few years from 1848 when he married a society beauty, Euphemia Chalmers Gray, and they lived in Mayfair, in the heart of fashionable London.

The marriage, it seems, was never consummated. In 854 Euphemia petitioned for divorce. The following year she married the Pre-Raphaelite artist Millais, whose reputation as a painter Ruskin has previously defended from stinging criticism to The Times newspaper.

By now Ruskin dictated art opinion to the extent that his views had considerable effect on saleroom prices. He was Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford (from 1870 to 1884), lectured widely, wrote extensively, and carried out the colossal task of arranged 19,000 drawings by Turner for the National Gallery.

However his opinion was not always welcomed. Ruskin reacted sharply to the work of the American artist James McNeil Whistler. He wrote, “I have never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of pain in the public’s face”. Whistler sued him for libel claiming, under cross examination, that the enormous sum was not just for two days work but for “the knowledge of a lifetime”: he was awarded damages of one farthing.

In reaction to the appalling social effects of the Industrial Revolution, Ruskin became a passionate advocate of what he termed, “the dignity and moral destiny of man”. In his writings he called, with typical zeal, for what are now commonplace reforms such as better housing and old age pensions. Leading by example, he funded many pensioners from his own personal fortune.

John Ruskin spent much of his life in a crusade to create “a greater awareness of beauty by an appeal to moral sense”. He died Edinburgh in January, 1900.

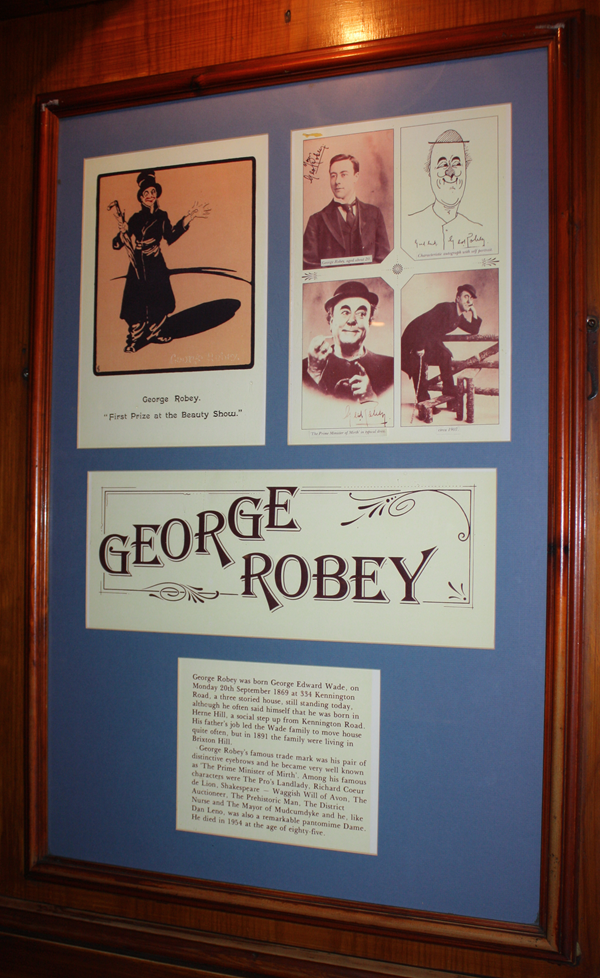

Framed photographs, drawings and text about George Robey.

The text reads: George Robey was born George Edward Wade, on Monday 20th September 1869 at 334 Kennington Road, a three storied house, still standing today, although he often said himself that he was born in Herne Hill, a social step up from Kennington Road. His father’s job led the Wade family to move house quite often, but in 1891 the family were living in Brixton Hill.

George Robey’s famous trade mark was his pair of distinctive eyebrows and he became very well known as ‘The Prime Minister of Mirth’. Among his famous characters were The Pro’s Landlady, Richard Coeur de Lion, Shakespeare – Waggish Will of Avon, The Auctioneer, The Prehistoric Man, The District Nurse and The Mayor of Mudcumdyke and he, like Dan Leno, was also a remarkable pantomime Dame. He died in 1954 at the age of eighty-five.

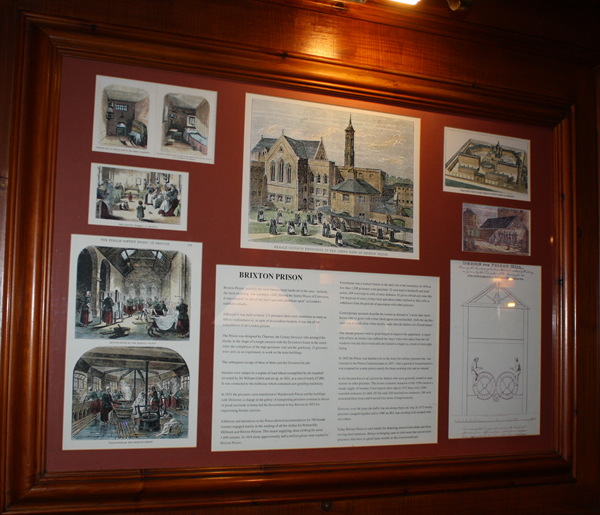

Framed drawings and text about Brixton prison.

The text reads: Brixton Prison, possibly the most famous local landmark in the area – certainly most enduring, was opened in 1820. Named the Surrey House of Correction, it was situated “in one of the most open and salubrious spots” in London’s southern suburbs.

Although it was built to house 175 prisoners there were sometimes as many as 400 in confinement so, in spite of its excellent location, it was one of the unhealthiest of all London prisons.

The Prison was designed by Chawner, the County Surveyor who arranged the blocks in the shape of a rough crescent with the Governor’s house in the centre. After the completion of the high perimeter wall and the gatehouse, 25 prisoners were sent, as an experiment, to work on the main buildings.

The subsequent escape of three of them cost the Governor his job.

Inmates were subject to a regime of hard labour exemplified by the treadmill invented by Sir William Cubitt and set up, in 1821, at a cost of nearly £7,000. It was connected to the millhouse which contained corn-grinding machinery.

In 1851 the prisoners were transferred to Wandsworth Prison and the buildings sold. However, a change in the policy of transporting prisoners overseas in favour of penal servitude at home led the Government to buy Brixton in 1853 for imprisoning female convicts.

Additions and alterations to the Prison allowed accommodation for 700 female inmates engaged mainly in the washing of all the clothes for Pentonville, Millbank and Brixton Prisons. This meant supplying clean clothing for some 1,800 inmates. In 1854 alone approximately half a million pieces were washed in Brixton Prison.

Punishment was a marked feature in the daily life of the institution. In 1854 no less than 1,209 prisoners were punished: 32 were kept in handcuffs and strait jacket, 238 were kept in cells of semi-darkness, 92 given a bread and water diet, 246 deprived of some of their food and others either confined to their cells or withdrawn from the periods of association with other prisoners.

Contemporary accounts describe the women dressed in “a loose dark claret-brown robe or gown with a blue cheek apron and neckerchief, while the cap they wore was of small close white muslin, made after the fashion of a French bonne”.

One female prisoner went to great lengths to improve her appearance. A report tells of how an inmate who stiffened her ‘stays’ with wires taken from her cell windows was not discovered until she fainted in a chapel as a result of extra tight lacing.

In 1882 the Prison was handed over to the Army for military prisoners but was returned to the Prison Commissioners in 1897. After a period of reconstruction it was reopened as a male prison mainly for those awaiting trial and on remand.

It also became known as a prison for debtors who were generally treated in the same manner as other prisoners. The severe economic recession of the 1930s ensured a steady supply of inmates. Court reports show that in 1932 there were 3.680 custodial sentences for debt. Of this total 258 received two sentences, 366 were sentenced three times and 6 served four terms of imprisonment.

However, over the years the traffic has not always been one way. In 1973 twenty prisoners escaped together and in 1980 and IRA man awaiting trial escaped with two others.

Today Brixton Prison is used mainly for detaining unconvicted adults and those serving short sentences. Delays in bringing cases to trial mean that unconvicted prisoners often have to spend many months in this overcrowded jail.

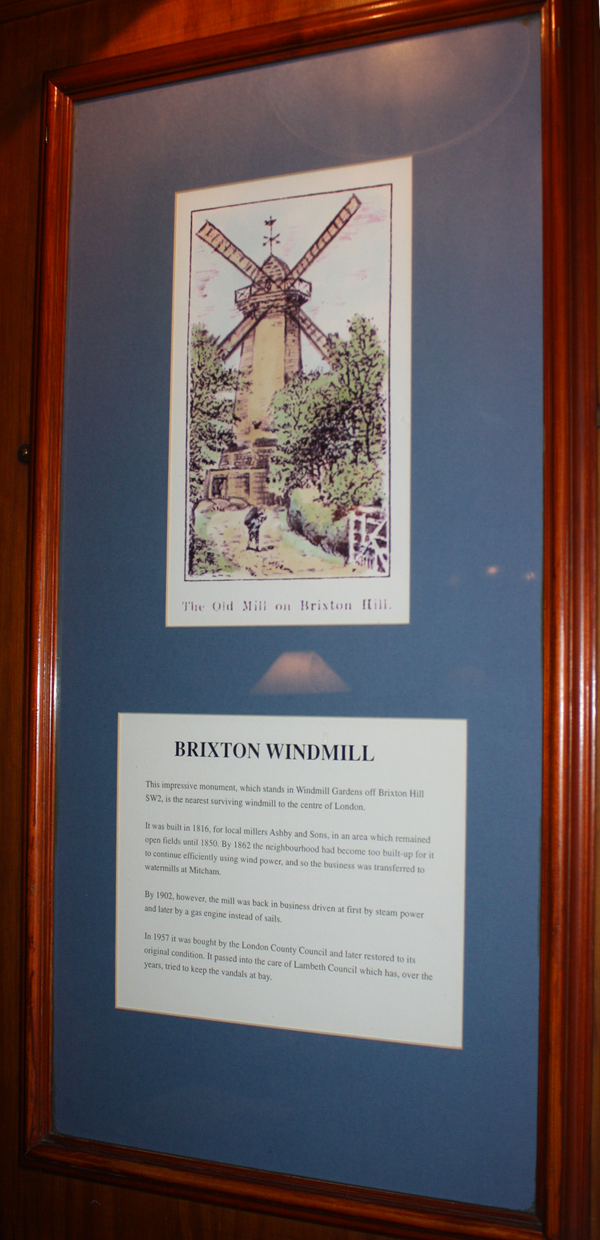

A framed drawing and text about the Brixton windmill.

The text reads: The impressive monument, which stands in Windmill Gardens off Brixton Hill SW2, is the nearest surviving windmill to the centre of London.

It was built in 1816, for local millers Ashby and Sons, in an area which remained open fields until 1850. By 1862 the neighbourhood had become too built-up for it to continue efficiently using wind power, and so the business was transferred to watermills at Mitcham.

By 1902, however, the mill was back in business driven at first by steam power and later by a gas engine stead of sails.

In 1957 it was bought by the London Country Council and later restored to its original condition. It passed into the care of Lambeth Council which has, over the years, tried to keep the vandals at bay.

A framed photograph of Electric Avenue, Brixton.

A framed photograph of Ace Lane, Brixton.

A framed photograph of Brixton Road c.1905.

A framed photograph of Brixton Road c.1905.

Framed photographs of Brixton Road.

A framed photograph of Electric Avenue c.1905.

A framed photograph of flower stalls under the viaduct c.1908.

A framed photograph of Coldharbour Lane.

A framed photograph of Atlantic Road c.1910.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.