Pub history

The George

This name recalls the centuries-old pub which stood on the corner of High Street and George Street. The latter took its name from this old inn, referred to as early as 1497, when it was called The George and Dragon.

17–21 George Street, Croydon, London, CR0 1LA

This name recalls the centuries-old pub which stood on the corner of High Street and George Street. The latter took its name from this old inn, referred to as early as 1497, when it was called The George and Dragon.

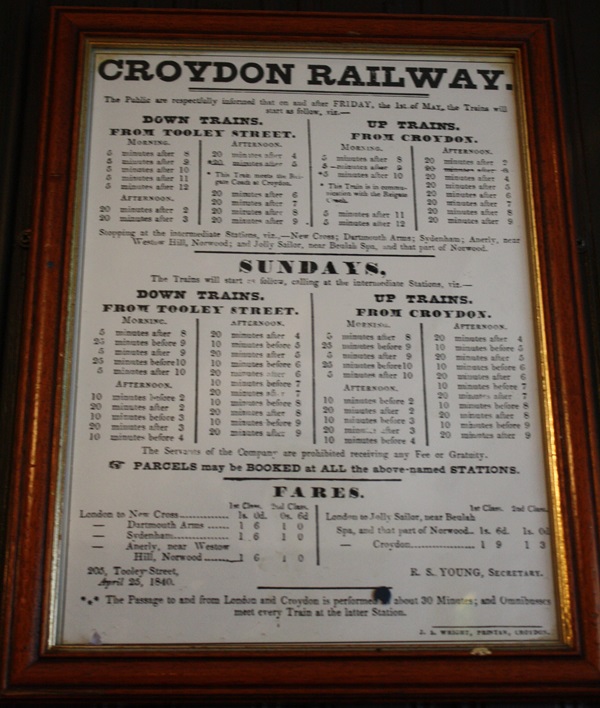

A framed copy of a Croydon railway timetable from 1840.

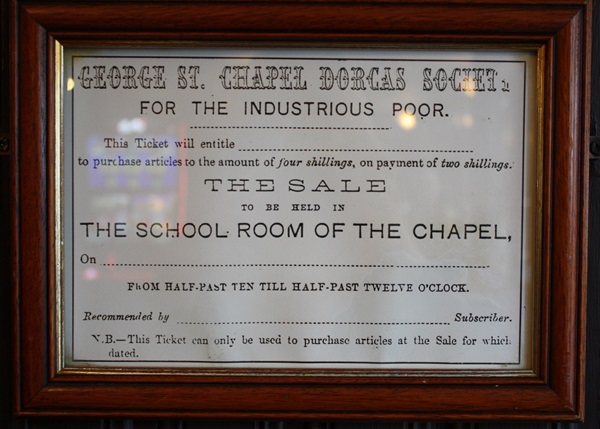

A framed copy of a ticket supplied by George Street Chapel Dorcas Society for the industrious poor.

This ticket allowed people to ‘purchase articles to the amount of four shillings, on payment of two shillings’.

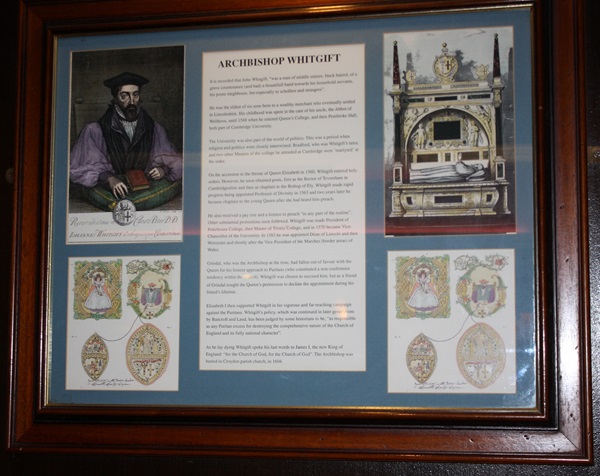

Framed drawings and print about Archbishop Whitgift.

The text reads: It is recorded that John Whitgift, “was a man of middle stature, black haired, of a grave countenance (and had) a bountiful hand towards his household servants, his poore neighbours, but especially to schollers and strangers”.

He was the eldest of six sons born to a wealthy merchant who eventually settled in Lincolnshire. His childhood was spent in the care of his uncle, the Abbot of Wellhove, until 1548 when he entered Queen’s College, and then Pembroke Hall, both part of Cambridge University.

The university was also part of the world of politics. This was a period when religion and politics were closely intertwined. Bradford, who was Whitgift’s tutor, and two other Masters of the college he attended at Cambridge were ‘martyred’ at the stake.

On the accession to the throne of Queen Elizabeth in 1560, Whitgift entered holy orders. However, he soon obtained posts, first as the Rector of Treversham in Cambridgeshire and then as chaplain to the Bishop of Ely. Whitgift made rapid progress being appointed Professor of Divinity in 1563 and two years later he became chaplain to the young Queen after she had heard him preach.

He also received a pay rise and a licence to preach “in any part of the realme”. Other substantial promotions soon followed. Whitgift was made President of Peterhouse College, then Master of Trinity College, and in 1570 became Vice-Chancellor of the University. In 1583 he was appointed Dean of Lincoln and then Worcester and shortly after the Vice-President of the Marches (border areas) of Wales.

Grindal, who was Archbishop at the time, had fallen out of favour with the Queen for his lenient approach to Puritans (who constituted a non-conformist tendency within the church). Whitgift was chosen to succeed him, but as a friend of Grindal sought the Queen’s permission to decline the appointment during his friend’s lifetime.

Elizabeth I then supported Whitgift in his vigorous and far-reaching campaign against the Puritans. Whitgift’s policy, which was continued in later generations by Bancroft and Paud, has been judged by some historians to be, “as responsible as any Puritan excess for destroying the comprehensive nature of the Church of England and its fully national character”.

As he lay dying Whitgift spoke his last words to James I, the new King of England: “for the Church of God, for the Church of God”. The Archbishop was buried in Croydon parish church, in 1604.

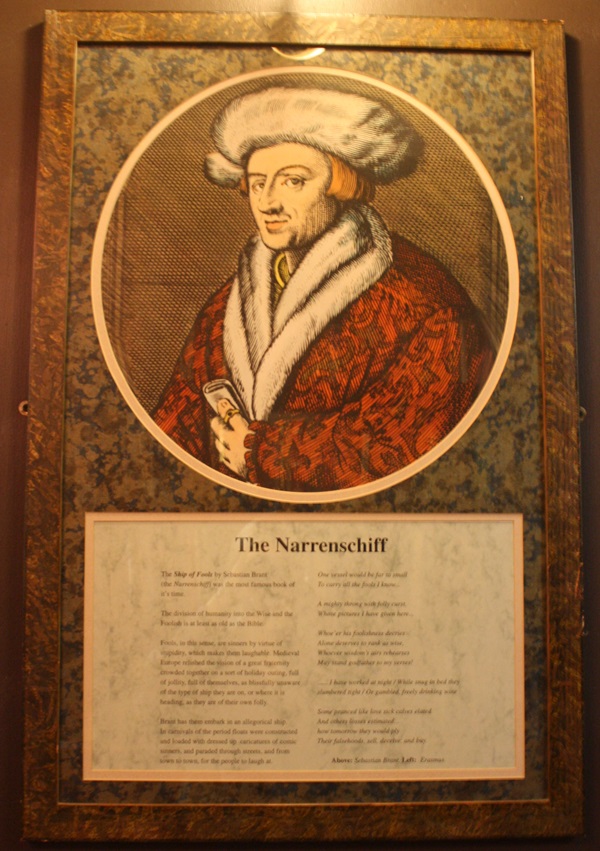

A framed print and text about Sebastian Brant.

The text reads: The Ship of Fools by Sebastian Brant (the Narrenschiff) was the most famous book of its time.

The division of humanity into the Wise and the Foolish is at least as old as the Bible.

Fools, in this sense, are sinners by virtue of stupidity, which makes them laughable. Medieval Europe relished the vision of a great fraternity crowded together on a sort of holiday outing, full of jollity, full of themselves, as blissfully unaware of the type of ship they are on, or where it is heading, as they are of their own folly.

Brant has them embark in an allegorical ship. In carnivals of the period floats were constructed and loaded with dressed up caricatures of comic sinners, and paraded through streets, and from town to town, for the people to laugh at.

One vessel would be far to small

To carry all the fools I know…

A mighty throng with folly curst

Whose pictures I have given here…

Whoe’er his foolishness decries

Alone deserves to rank as wise

Whoever wisdom’s airs rehearses

May stand godfather to my verses!

…… I have worked at night / While snug in bed they slumbered tight / Or gambled freely drinking wine

Some pranced like love sick calves elated

And others losses estimated…

How tomorrow they would ply

Their falsehoods, sell deceive, and buy.

Above: Sebastian Brant

Left: Erasmus

Framed prints and text about Jabez Balfour and Charles Haddon Spurgeon.

The text reads:

Corruption…

Jabez Balfour moved to Wilton Lodge, London Road, Croydon, in 1869, becoming Croydon’s first Mayor in 1883.

In 1868 Balfour helped found the Liberator Building Society, and by 1870 he was managing Director. The name was chosen to suggest an association with the Non-Conformist (Low Church Radical) organisation the Liberation Society, and clergymen were recruited to sell shares.

Financial tricks were used to divert funds into the pockets of Balfour, and others, and in 1892 the company collapsed with the massive debts of over £7 million.

Balfour escaped to Argentina, but was extradited, tried for fraud, and sentenced to 14 years hard labour. He was released in 1906, and wrote a book called My Prison Life.

…and regeneration

Spurgeon’s Tabernacle, West Croydon’s most prominent Baptist Chapel, was completed in 1873, and stood at the southern end of Whitehorse Lane.

Charles Haddon Spurgeon made his name as a Baptist preacher. He drew such large crowds that in 1859-61 the Metropolitan Tabernacle, seating 6000, and also began the college named after him in his home at Beulah Hill.

In 1887 he left the Baptist Union. Some 50 Volumes of his sermons were collected, and he wrote many other works, including collections of sayings called John Ploughman’s Talk.

Left and Top Left: Jabez Balfour.

Top Right: Charles Haddon Spurgeon.

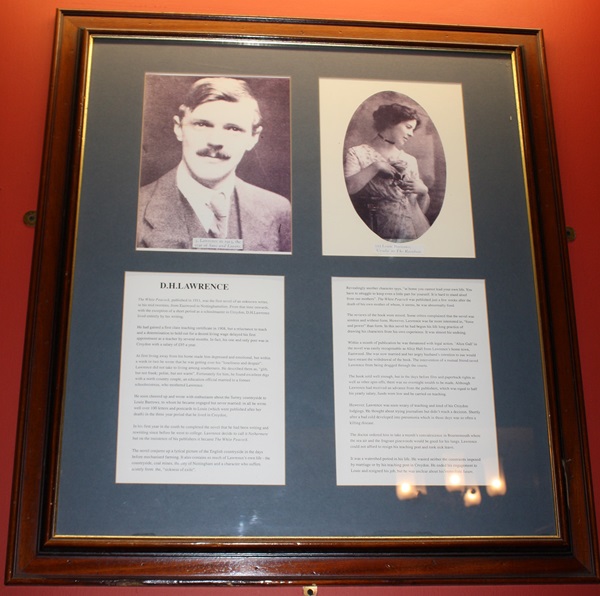

Framed photographs and text about DH Lawrence.

The text reads: The White Peacock, published in 1911, was the first novel of an unknown writer, in his mid-twenties, from Eastwood in Nottinghamshire. From that time onwards, with the exception of a short period as a schoolmaster in Croydon, D.H.Lawrence lived entirely by his writing.

He gained a first class teaching certificate in 1908, but a reluctance to teach and a determination to hold out for a decent living wage delayed his first appointment as a teacher by several months. In fact, his one and only post was in Croydon with a salary of £95 a year.

At first living away from his home made him depressed and emotional, but within a week or two he wrote that he was getting over his “loneliness and despair”. Lawrence did not take to living among southerners. He described them as, “glib, but not frank; polite, but not warm”. Fortunately for him, he found excellent digs with a north country couple, an education official married to a former schoolmistress, who mothered Lawrence.

He soon cheered up and wrote with enthusiasm about the Surrey countryside to Louie Burrows, to whom he became engaged but never married: in all he wrote well over 100 letters and postcards to Louie (which were published after her death) in the three year period that he lived in Croydon.

In his first year in the south he completed the novel that he had been writing and rewriting since before he went to college. Lawrence decided to call it Nethermere but on the insistence of his publishers it became The White Peacock.

The novel conjured up a lyrical picture of the English countryside in the days before mechanised farming. It also contains so much of Lawrence’s own life – the countryside, coal mines, the city of Nottingham and a character who suffers acutely from the, “sickness of exile”.

Revealing another character says “at home you cannot lead your own life. You have to struggle to keep even a little part for yourself. It is hard to stand aloof from our mothers”. The White Peacock was published just a few weeks after the death of his own mother of whom, it seems, he was abnormally fond.

The reviews of the book were mixed. Some critics complained that the novel was aimless and without form. However, Lawrence was far more interested in, “force and power” than form. In this novel he had begun his lifelong practice of drawing his characters from his own experience. It was almost his undoing.

Within a month of publication he was threatened with legal action. ‘Alice Gall’ in the novel was easily recognisable as Alice Hall from Lawrence’s home town, Eastwood. She was now married and her angry husband’s intention to sue would have meant the withdrawal of the book. The intervention of a mutual friend saved Lawrence from being dragged through the courts.

The book sold well enough, but in the days before film and paperback rights as well as other spin-offs, there was no overnight wealth to be made. Although Lawrence had received an advance from the publishers, which was equal to half his yearly salary, funds were low and he carried on teaching.

However, Lawrence was soon weary of teaching and tired of his Croydon lodgings. He thought about trying journalism but didn’t reach a decision. Shortly after, a bad cold developed into pneumonia which in those days was so often a killing disease.

The doctor ordered him to take a month’s convalescence in Bournemouth where the sea air and the fragrant pinewoods would be good for his lungs. Lawrence could not afford to resign his teaching post and took sick leave.

It was a watershed period in his life. He wanted neither the constraints imposed by marriage or by his teaching post in Croydon. He ended his engagement to Louie and resigned his job, but he was unclear about his immediate future.

Framed photographs of East Croydon Station.

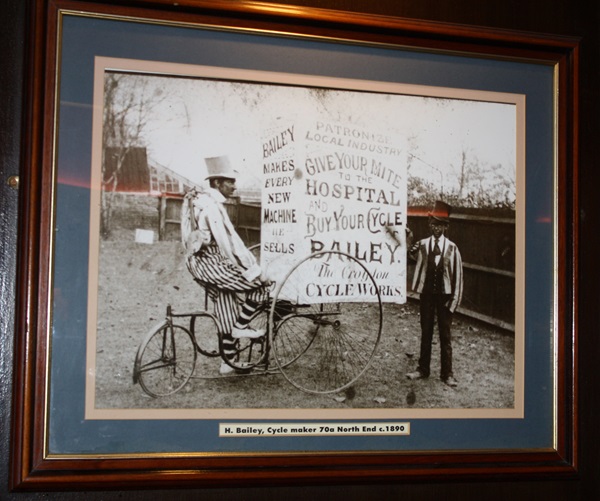

A framed photograph of H Bailey, cycle-maker 70a North End, c1890.

A framed photograph of High Street, c1908.

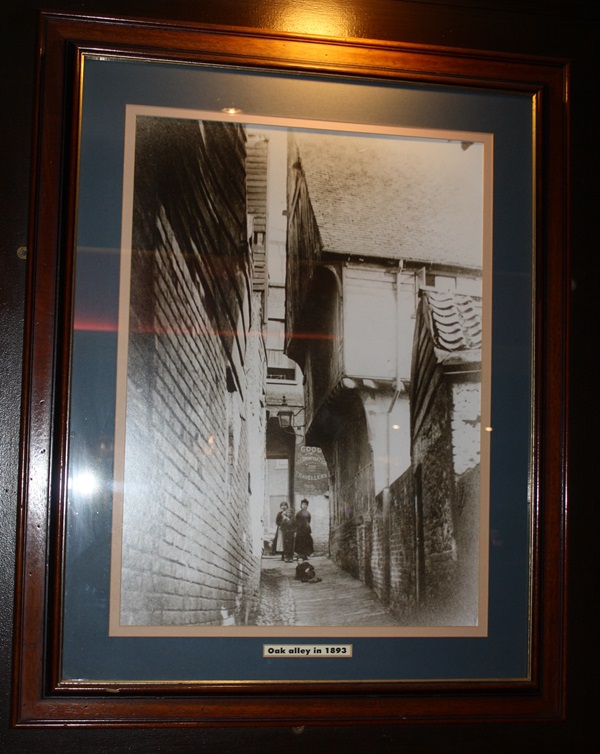

A framed photograph of Oak Alley in 1893.

A framed photograph of Purley Way swimming pool – opened in 1935 and closed in 1979.

A framed photograph of Church Street, Croydon.

A photograph of where The George and Dragon once stood.

External photograph of the building – front.