Pub history

The Liberty Bounds

This pub is located just outside the boundary of the area, or liberty, controlled by the City of London. The pub stands close to the site of the scaffold where many prisoners from the Tower of London met their fate in the 16th and 17th century.

15 Trinity Square, Tower Hill, Tower of London, London, EC3N 4AA

This pub is located just outside the boundary of the area, or liberty, controlled by the City of London. The pub stands close to the site of the scaffold where many prisoners from the Tower of London met their fate in the 16th and 17th century.

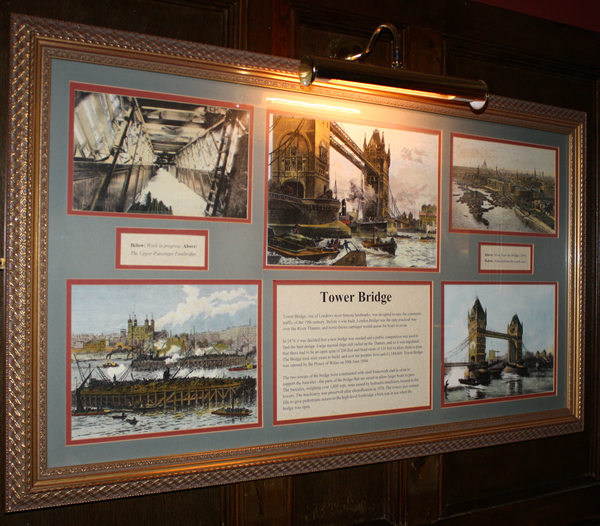

A framed collection of illustrations, prints and text about Tower Bridge.

The text reads: Tower Bridge, one of London’s most famous landmarks, was designed to ease the commuter traffic of the 19th century. Before it was built, London Bridge was the only practical way over the River Thames, and horse drawn carriages would queue for hours to cross.

In 1876 it was decided that a new bridge was needed and a public competition was used to find the best design. Large masted ships still sailed up the Thames, and so it was stipulated that there had to be an open span of 200 feet and head room of 135 feet to allow them to pass. The bridge took nine years to build, and cost ten peoples lives and £1,184,000. Tower Bridge was opened by the Prince of Wales on 30th June 1894.

The towers of the bridge were constructed with steel framework clad in stone to support the bascules – the parts of the bridge that are raised to allow larger boats to pass. The bascules, weighing over 1,00 tons, were raised by hydraulic machinery housed in the towers. The machinery was preserved after electrification in 1976. The towers also contain lifts to give pedestrians access to the high-level footbridge which was in use when the bridge was open.

The illustrations are captioned: (top left) ‘The Upper Passenger Footbridge’; (bottom left) ‘Work in progress’; (top right) ‘View from the Bridge, 1894’; (bottom right) ‘Viewed from the south east’.

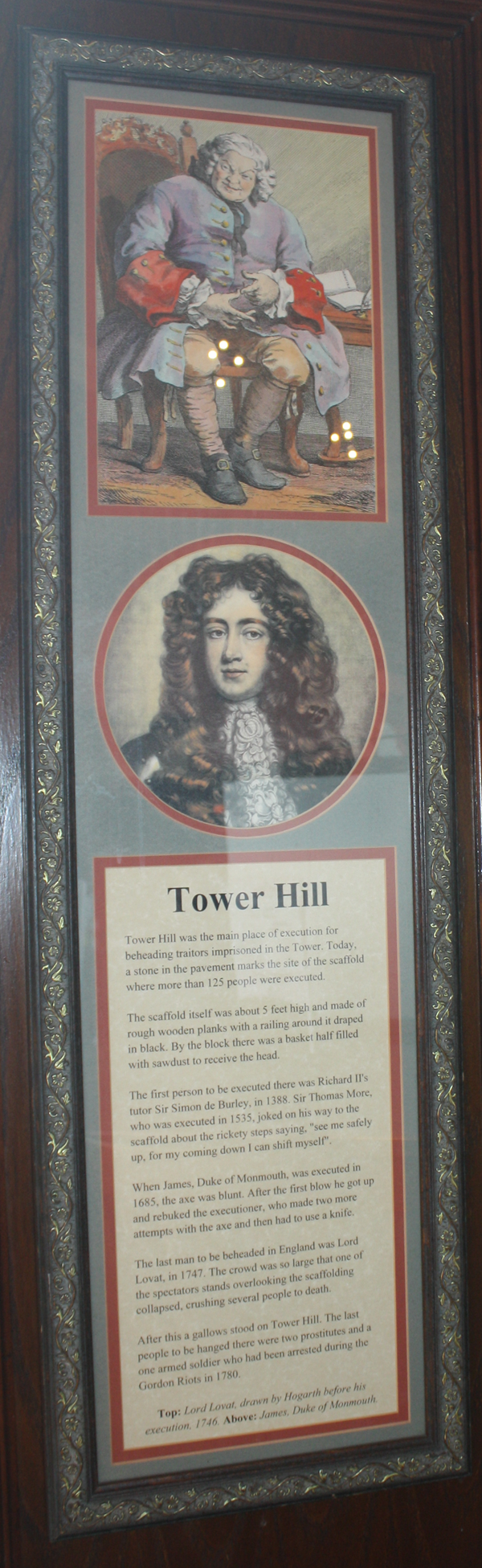

A framed collection of prints and text about Tower Hill.

The text reads: Tower Hill was the main place of execution for beheading traitors imprisoned in the Tower. Today, a stone in the pavement marks the site of the scaffold where more than 125 people were executed.

The scaffold itself was about 5 feet high and made of rough wooden planks with a railing around it draped in black. By the block there was a basket half filled with sawdust to receive the head.

The first person to be executed there was Richard II’s tutor Sir Simon de Burley, in 1388. Sir Thomas More, who was executed in 1535, joked on his way to the scaffold about the rickety steps saying, “see me safely up, for my coming down I can shift myself”.

When James, Duke of Monmouth, was executed in 1685, the axe was blunt. After the first blow he got up and rebuked the executioner, who made two more attempts with the axe and then had to use a knife.

The last man to be beheaded in England was Lord Lovat, in 1747. The crowd was so large that one of the spectators stands overlooking the scaffolding collapsed, crushing several people to death.

After this a gallows stood on Tower Hill. The last people to be hanged there were two prostitutes and a one armed soldier who had been arrested during the Gordon Riots in 1780.

Top: Lord Lovat, drawn by Hogarth before his execution, 1746. Above: James, Duke of Monmouth.

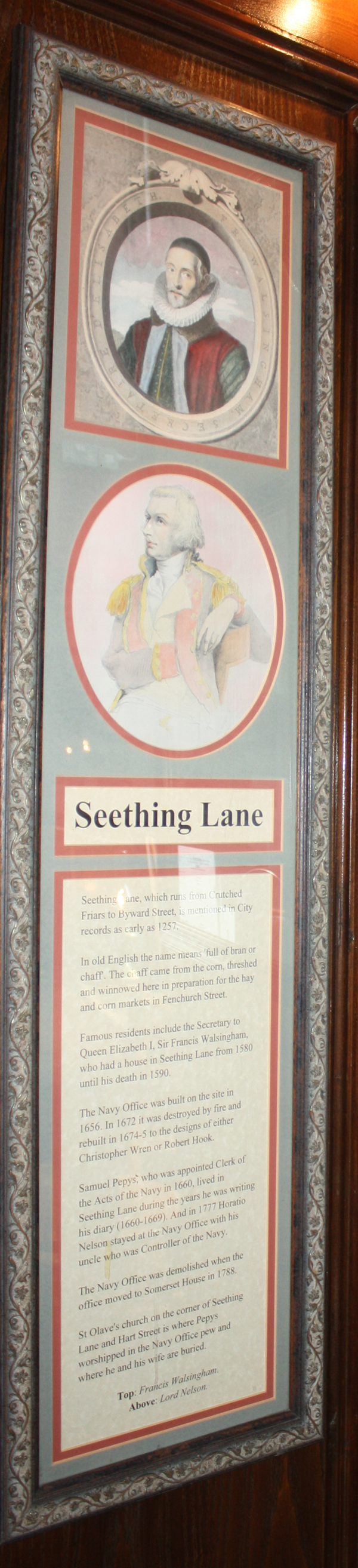

A framed collection of prints and text about Seething Lane.

The text reads: Seething Lane, which runs from Crutched Friars to Byward Street, is mentioned in City records as early as 1257.

In old English the name means ‘full of bran or chaff’. The chaff came from the corn, threshed and winnowed here in preparation for the hay and corn markets in Fenchurch Street.

Famous residents include the Secretary to Queen Elizabeth I. Sir Francis Walsingham, who had a house in Seething Lane from 1580 until his death in 1590.

The Navy Office was built on the site in 1656. In 1672 it was destroyed by fire and rebuilt in 1674-5 to the designs of either Christopher Wren or Robert Hook.

Samuel Pepys, who was appointed Clerk of the Acts of the Navy in 1660, lived in Seething Lane during the years he was writing his diary (1660-1669). And in1777 Horatio Nelson stayed at the Navy office with his uncle who was Controller of the Navy.

St Olave’s church on the corner of Seething Lane and Hart Street is where Pepys worshipped in the Navy Office pew and where he and his wife are buried.

Top: Francis Walsingham

Above: Lord Nelson.

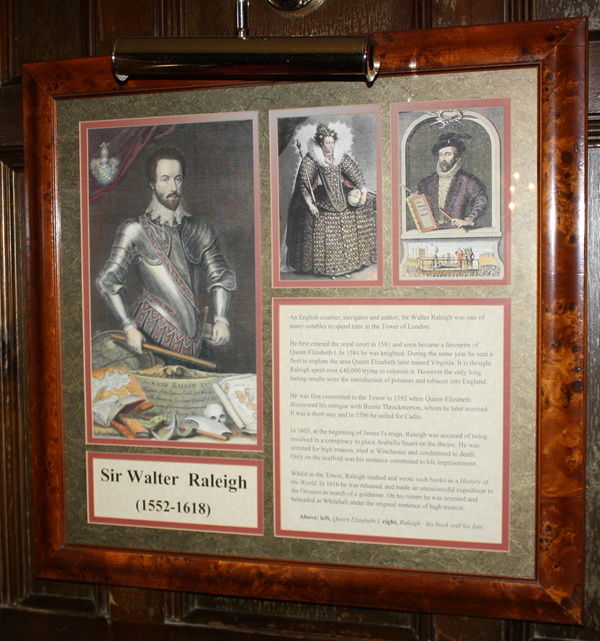

A framed collection of prints and text about Sir Walter Raleigh (1552–1618).

The text reads: An English courtier, navigator and wuthor, Sir Walter Raleigh was one of many notables to spend time in the Tower of London.

He first entered the royal court in 1581 and soon became a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. In 1584 he was knighted. During the same year he sent a fleet to explore the area Queen Elizabeth later named Virginia. It is thought Raleigh spent over £40,000 trying to colonise it. However the only long lasting results were the introduction of potatoes and tobacco into England.

He was first commited to the Tower in 1592 when Queen Elizabeth discovered his intrigue with Bessie Throckmorton, whom he later married. It was a short stay and in 1596 he sailed for Cadiz.

In 1603, at the beginning of James I’s reign, Raleigh was accused of being involved in a conspiracy to place Arabella Stuart on the throne. He was arrested for high treason, tried at Winchester and condemned to death. Only on the scaffold was his sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

Whilst in the Tower, Raleigh studied and wrote such books as a History of the World. In 1616 he was released, and made an unsuccessful expedition to the Orinoco in search of a goldmine. On his return he was arrested and beheaded at Whitehall under the original sentence of high treason.

Above: left, Queen Elizabeth I, right, Raleigh – his book and his fate.

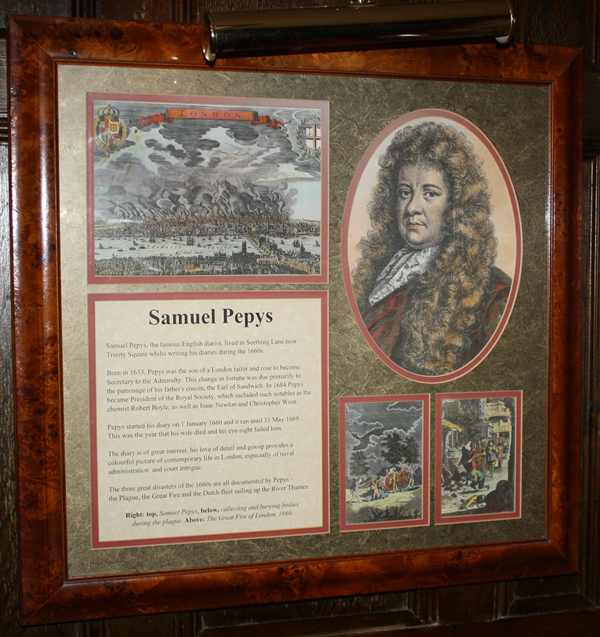

A framed collection of prints and text about Samuel Pepys.

The text reads: Samuel Pepys, the famous English diarist, lived in Seething Lane near Trinity Square whilst writing his diaries during the 1660s.

Born in 1633, Pepys was the son of a London tailor and rose to become Secretary to the Admiralty. This change in fortune was due primarily to the patronage of his father’s cousin, the Earl of Sandwich. In 1684 Pepys became President of the Royal Society, which included such notables as the chemist Robert Boyle , as well as Isaac Newton and Christopher Wren.

Pepys started his diary on 1 January 1660 and it ran until 31 May 1669. This was the year that his wife died and his eye-sight failed him.

The diary is of great interest, his love of detail and gossip provides a colourful picture of contemporary life in London, especially of naval administration and court intrigue.

The three great disasters of the 1660s are all documented by Pepys – the Plague, the Great Fire and the Dutch fleet sailing up the River Thames.

Right: top, Samuel Pepys, below, collecting and burying bodies during the plague. Above: The Great Fire of London, 1666.

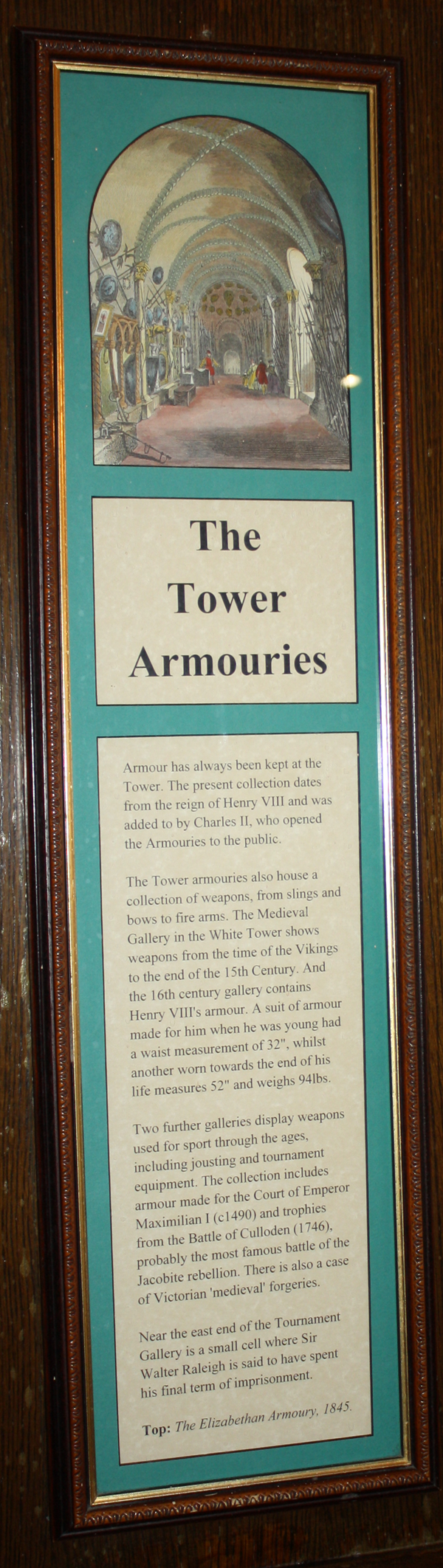

A framed illustration and text about the Tower Armouries.

The text reads: Armour has always been kept at the Tower. The present collection dates from the reign of Henry VIII and was added to by Charles Il, who opened the Armouries to the public.

The Tower armouries also house a collection of weapons from slings and bows to tire arms. The Medieval Gallery in the White Tower shows weapons from the time of the Vikings to the end of the 15th Century. And the 16th century gallery contains Henry VIII’s armour. A suit of armour made for him when he was young had a waist measurement of 32”, whilst another worn towards the end of his life measures 52” and weighs 94Ibs.

Two further galleries display weapons used for sport through the ages, including jousting and tournament equipment. The collection includes armour made for the Court of Emperor Maximilian I (c1490) and trophies from the Battle of Culloden (1746), probably the most famous battle of the Jacobite rebellion. There is also a case of Victorian ‘medieval’ forgeries.

Near the east end of the Tournament Gallery is a small cell where Sir Walter Raleigh is said to have spent his final term of imprisonment.

Top: The Elizabethan Armoury, 1845.

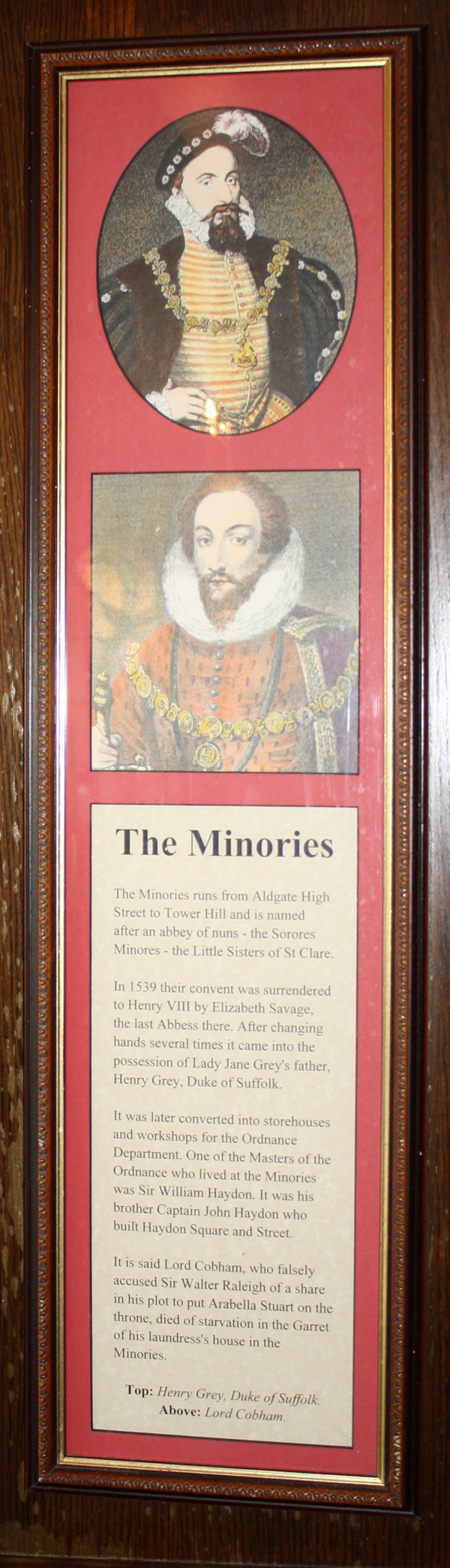

A framed collection of prints and text about The Minories.

The text reads: The Minories runs from Aldgate High Street to Tower hill and is named after an abbey of nuns – the Sorores Minores – the Little Sisters of St Clare.

In 1539 their convent was surrendered to Henry VIII by Elizabeth Savage, the last Abbess there. After changing hands several times it came into the possession of Lady Jane Grey’s father, Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk.

It was later converted into storehouses and workshops for the Ordnance Department. One of the Masters of the Ordnance who lived at the Mionries was Sir William Haydon. It was his brother Captain John Haydon who built Haydon Square and Street.

It is said Lord Cobham, who falsely accused Sir Walter Raleigh of a share in his plot to put Arabella Stuart on the throne, died of starvation in the Garret of his laundress’s house in the Minories.

Top: Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk Above: Lord Cobham.

A framed collection of prints and text about the history of the area.

The text reads: The neighbourhood around the Tower of London is full of historic interest.

The founder of Pennsylvania, William Penn was born in his father’s house on Tower Hill in 1644.

It was in a cutler’s shop on Tower Hill that John Felton bought the knife with which he killed King Charles I’s favourite, the Duke of Buckingham.

Edmund Spenser, the great English poet, was born here in 1552.

The old Czar of Muscovy pub recalled Peter the Great’s presence here whilst learning the art of shipbuilding.

John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal, set up his first Observatory in White Tower.

Top: John Felton imprisoned in the Tower

Above: John Flamsteed.

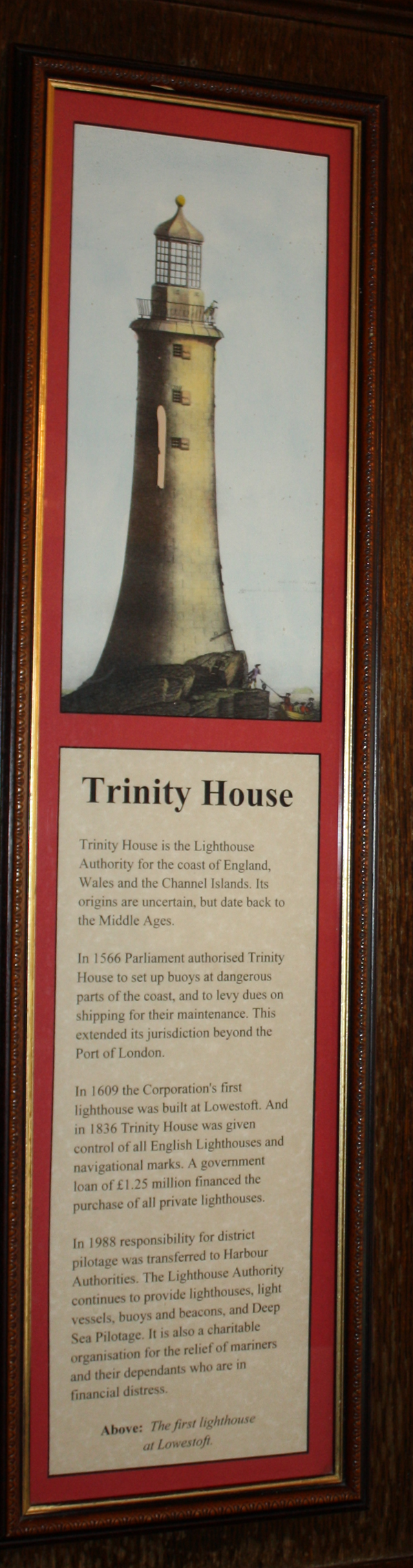

A framed print and text about Trinity House.

The text reads: Trinity House is the Lighthouse Authority for the Coast of England, wales and the Channel Islands. Its origins are encertain, but date back to the Middle Ages.

In 1566 Parliament authorised Trinity House to set up buoys at dangerous parts of the coast, and to levy dues on shipping for their maintenance. This extended its jurisdiction beyond the Port of London.

In 1609 the Corporation’s first lighthouse was built at Lowestoft. And in 1836 Trinity House was given control of all English Lighthouses and navigational marks. A government loan of £1.25 million financed the purchase of all private lighthouses.

In 1988 responsibility for district pilotage was transferred to Harbour Authorities. The Lighthouse Authority continues to provide lighthouses, light vessels, buoys and beacons, and Deep Sea Pilotage. It is also a charitable organisation for the relief of mariners and their dependents who are in financial distress.

Above: The first lighthouse at Lowestoft.

A framed print and text about America Square and the Rothschilds.

The text reads: America Square, bordered by Crosswall and Fenchurch Street Station, was built between 1768 and 1774, at the same time as the Circus and Crescent. It was designed by George Dance the Younger, and was based on Grosvenor and Cavendish Squares.

The residents were mainly merchants and sea captains many of whom had dealings with America, so giving the Square its name.

It remained unscathed until the development of the London and Blackwall Railway in 1836. Then in 1941 it was bombed, and today none of the original houses remain.

The Square’s most famous resident was Baron Meyer de Rothschild, a member of the famous banking family. He bought and built on a plot of land between Royal Mint Street and St Katherines Dock.

He purchased a second site near Aldgate for his 4% Industrial Dwellings Company – originally founded to provide homes for Jewish artisans. The development was known as the Charlotte de Rothschild Dwellings.

Top: Baron Rothschild out riding.

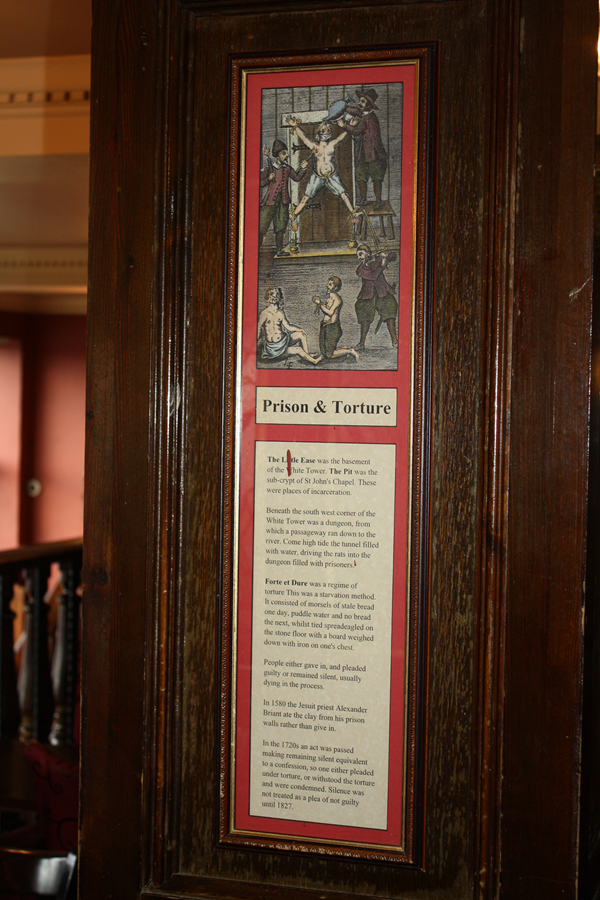

A framed print and text about prison and torture.

The text reads: The Little Ease was the basement of the White Tower. The Pit was the sub-crypt of St John’s Chapel. These were places of incarceration.

Beneath the south west corner of the White Tower was a dungeon, from which a passageway ran down to the river. Come high tide the tunnel filled with water, driving the rats into the dungeon filled with prisoners.

Forte et Dure was a regime of torture. This was a starvation method. It consisted of morsels of stale bread one day, puddle water and no bread the next, whilst tied spreadeagled on the stone floor with a board weighed down with iron on one’s chest.

People either gave in, and pleaded guilty or remained silent, usually dying in the process. In 1580 the Jesuit priest Alexander Briant ate the clay from his prison walls rather than give in.

In the 1720s an act was passed making remaining silent equivalent to a confession, so one either pleaded under torture, or withstood the torture and were condemned. Silence was not treated as a plea of guilty until 1827.

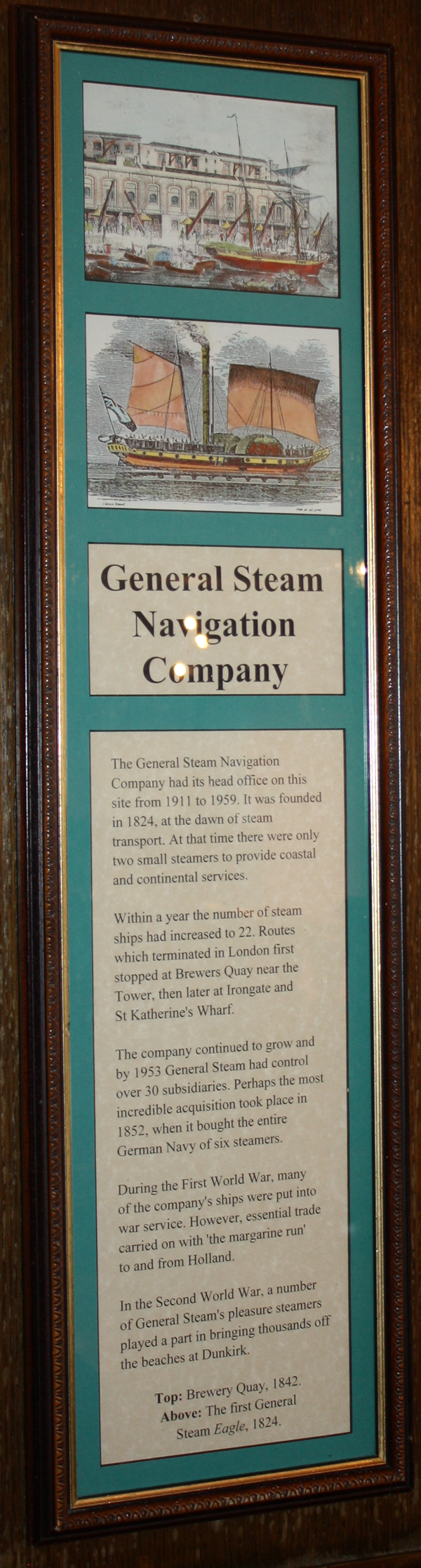

A framed collection of illustrations and text about the General Steam Navigation Company.

The text reads: The General Steam Navigation Company had its head office on this site from 1911 to 1959. It was founded in 1824, at the dawn of steam transport. At that time there were only two small steamers to provide coastal and continental services.

Within a year the number of steam ships had increased to 22. Routes which terminated in London first stopped at Brewers Quay near the Tower, then later at Irongate and St Katherine’s Wharf.

The company continued to grow and by 1953 General Steam had control over 30 subsidiaries. Perhaps the most incredible acquisition took place in 1852, when it bought the entire German Navy of six steamers.

During the First World War, many of the company’s ships were put into war service. However, essential trade carried on with ‘the margarine run’ to and from Holland.

In the Second World War, a number of General Steam’s pleasure steamers played a part in bringing thousands off the beaches at Dunkirk.

Top: Brewery Quay, 1842.

Above: The first General Steam Eagle, 1824.

A framed collection of prints, illustrations and text about The Custom House.

The text reads: The first Custom House was built in 1275 on the Old Wool Quay east of its present position in Lower Thames Street. The Custom House has been rebuilt several times, notably by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire, between 1668-72. In 1714 it was severely damaged when a store of gun powder blew up near by. The new building was designed by Thomas Ripley, who introduced the Long Room where customs men received official documents.

In 1813 David Laing, who was surveyor of buildings to the Board of Customs, started to build a larger Custom House on a site to the west of the old one. It was completed in 1817. However in 1825 part of the Long Room collapsed into the warehousing below. This was caused by rotten beech pilings, and resulted in Laing’s dismissal. An imposing new river façade and Long Room were built by Robert Smike at a cost of £200, 000. During the Second World War the east wing suffered bomb damage and was rebuilt to the original plans.

Left: The Custom House in Elizabeth I’s reign

Right: The Custom House, 1739

Above: left, the Custom House, 1808, centre, the new Custom House, right, Christopher Wren.

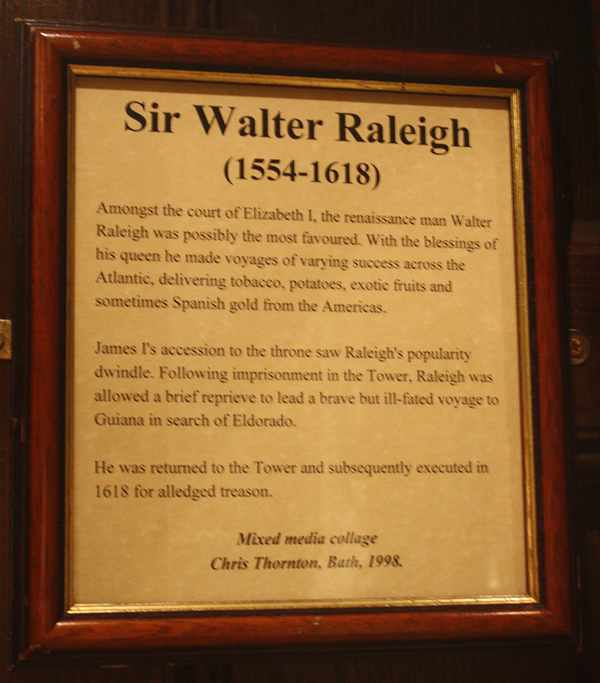

A framed passage of text about Sir Walter Raleigh (1554–1618).

The text reads: Amongst the court of Elizabeth I, the renaissance man Walter Raleigh was possibly the most favoured. With the blessings of his queen he made voyages of varying success across the Atlantic, delivering tobacco, potatoes, exotic fruits and sometimes Spanish gold from the Americas.

James I’s accession to the throne saw Raleigh’s popularity dwindle. Following imprisonment in the Tower, Raleigh was allowed a brief reprieve to lead a brave but ill-fated voyage to Guiana in search of Eldorado.

He was returned to the Tower and subsequently executed in 1618 for alledged treason.

Mixed media collage Chris Thornton, Bath, 1998.

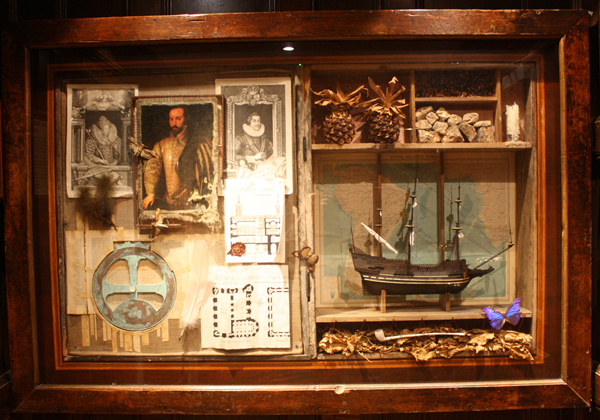

A framed collection of photos and artefacts commemorating the life and travels of Sir Walter Raleigh.

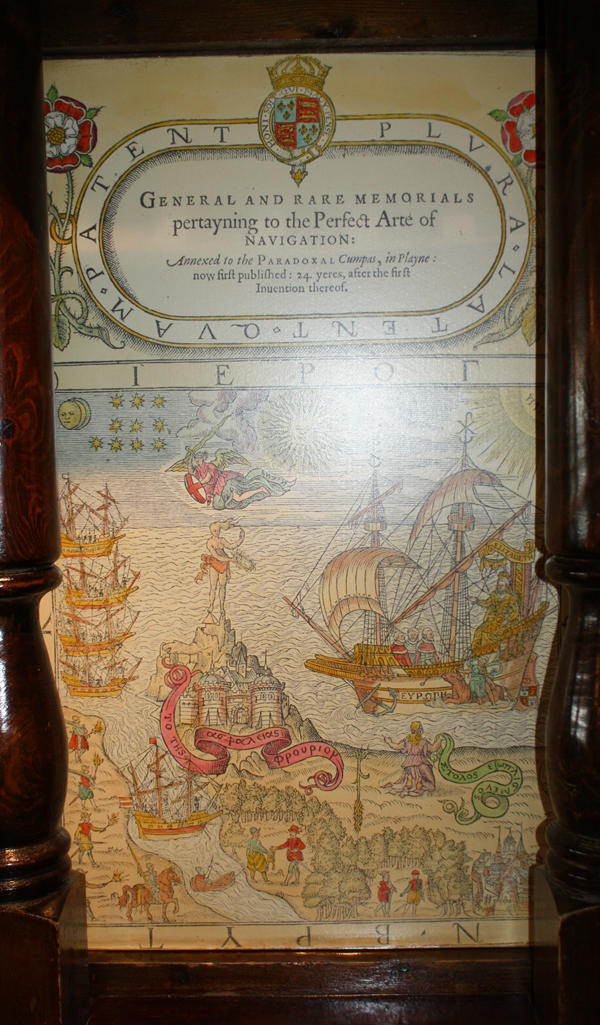

An illustration commemorating various voyages.

A mural depicting the tower of London.

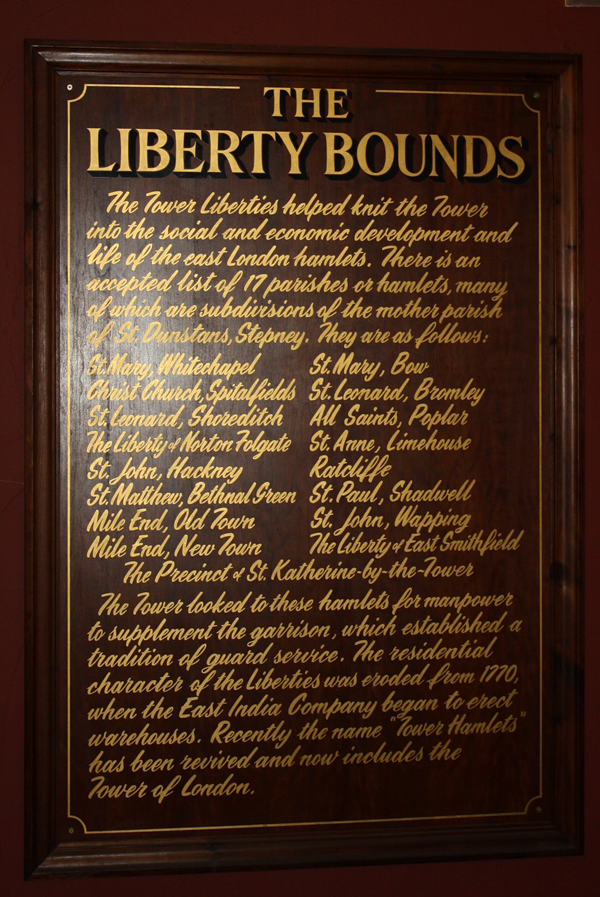

A passage of text telling of the various London parishes during the 1500s.

The text reads: The Tower Liberties helped knit the Tower into the social and economic development and life of the east London hamlets. There is an accepted list of 17 parishes or hamlets, many of which are subdivisions of the mother parish of St. Dunstans, Stepney. They are as follows:

St. Mary, Whitechapel; Christ Church, Spitalfields; St. Leonard, Shoreditch; The Liberty of Norton Folgate; St. John, Hackney; St. Matthew, Bethnal Green; Mile End, Old Town; Mile End, New Town; St. Mary, Bow; St. Leonard, Bromley; All Saints, Poplar; St. Anne, Limehouse Ratcliffe; St. Paul, Shadwell; St. John, Wapping; The Liberty of East Smithfield; The Precinct of St. Katherine-by-the-Tower.

The Tower looked to these hamlets for manpower to supplement the garrison, which established a tradition of guard service. The residential character of the Liberties was eroded from 1770, when the East India Company began to erect warehouses. Recently the name “Tower Hamlets” has been revived and now includes the Tower of London.

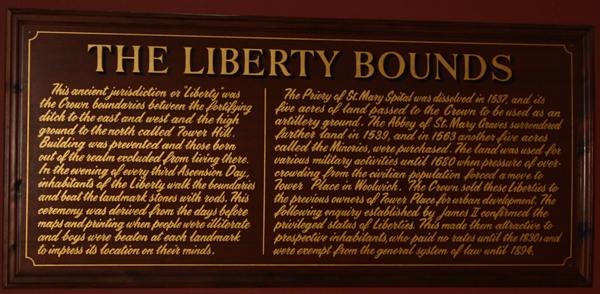

A passage of text recounting the local area.

The text reads: This ancient jurisdiction or “Liberty” was the Crown boundaries between the fortifying ditch to the east and west and the high ground to the north called Tower Hill. Building was prevented and those born out of the realm excluded from living there. In the evening of every third Ascension Day, inhabitants of the Liberty walk the boundaries and beat the landmark stones with rods. This ceremony was derived from the days before maps and printing when people were illiterate and boys were beaten at each landmark to impress its location on their minds.

The Priory of St. Mary Spital was dissolved in 1537, and its five acres of land passed to the Crown to be used as an artillery ground. The Abbey of St. Mary Graves surrendered further land in 1539, and in 1563 another five acres called the Minories, were purchased. The land was used for various military activities until 1680 when pressure of overcrowding from the civilian population forced to move to Tower Place in Woolwich. The Crown sold these Liberties to the previous owners of Tower Place for urban development. The following enquiry established by James II confirmed the privileged status of Liberties. This made them attractive to prospective inhabitants, who paid no rates until the 1830s and were exempt from the general system of law until 1894.

A replica of one of the landmark stones which would be beaten with rods.

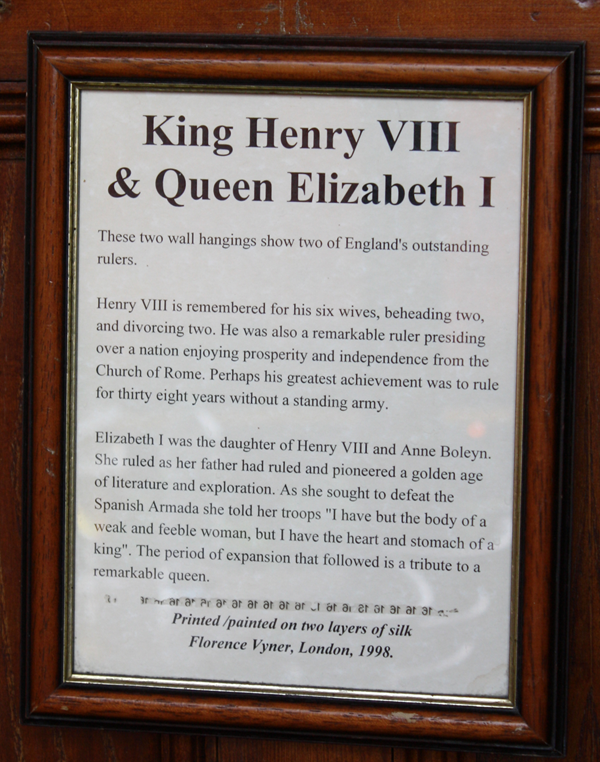

A framed passage of text about King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I.

The text reads: These two wall hangings show two of England’s outstanding rulers.

Henry VIII is remembered for his six wives, beheading two, and divorcing two. He was also a remarkable ruler presiding over a nation enjoying prosperity and independence from the Church of Rome. Perhaps his greatest achievement was to rule for thirty eight years without a standing army.

Elizabeth was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. She ruled as her father had ruled and pioneered a golden age of literature and exploration. As she sought to defeat the Spanish Armada she told her troops “I have but the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king”. The period of expansion that followed is a tribute to a remarkable queen.

A dress designed to commemorate Queen Elizabeth I. Printed/painted on two layers of silk; Florence Vyner, London, 1998.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.