Pub history

The Surrey Docks

The name of this pub recalls the Surrey Commercial Docks, located in this area from 1807 to 1970. There were 10 docks in all, covering 372 acres, including the reconstructed Greenland Dock, to the rear of this pub.

185 Lower Road, Rotherhithe, London, SE16 2LW

The name of this pub recalls the Surrey Commercial Docks, located in this area from 1807 to 1970. There were 10 docks in all, covering 372 acres, including the reconstructed Greenland Dock, to the rear of this pub.

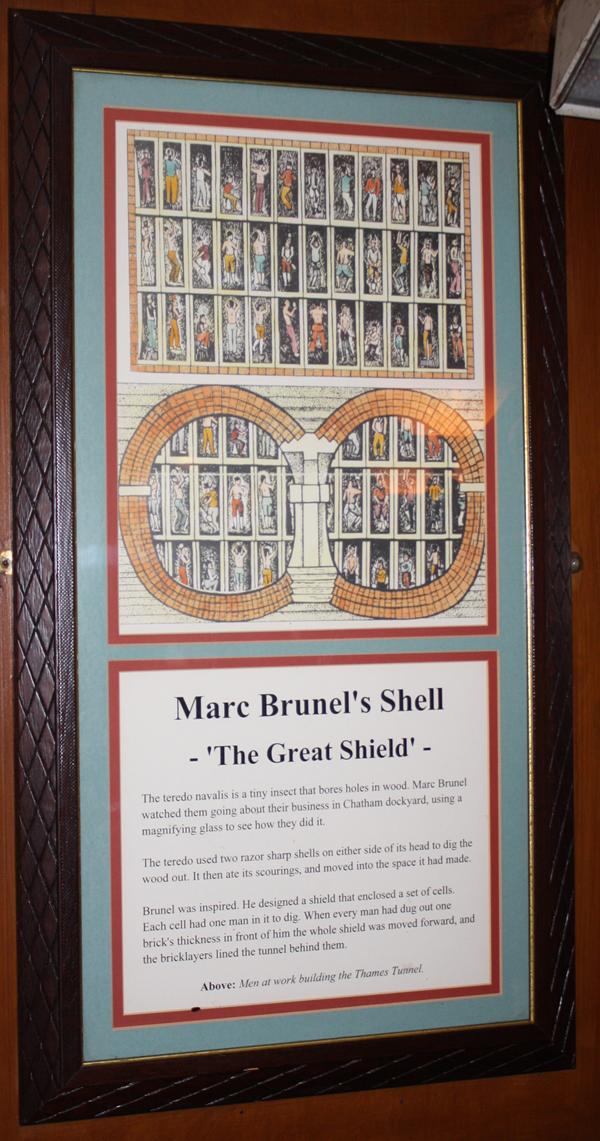

A framed drawing and text about Marc Brunel’s shell – ‘The Great Shield’.

The text reads: The teredo navalis is a tiny insect that boresholes in wood. Marc Brunel watched them going about their business in Chatham dockyard, using a magnifying glass to see how they did it.

The teredo used two razor sharp shells on either side of its head to dig the wood out. It then ate its scourings, and moved into the space it had made.

Brunel was inspired. He designed a shield that enclosed a set of cells. Each cell had one man in it to dig. When every man had dug out one brick’s thickness in front of him the whole shield was moved forward, and the bricklayers lined the tunnel behind them.

Above: Men at work building the Thames Tunnel.

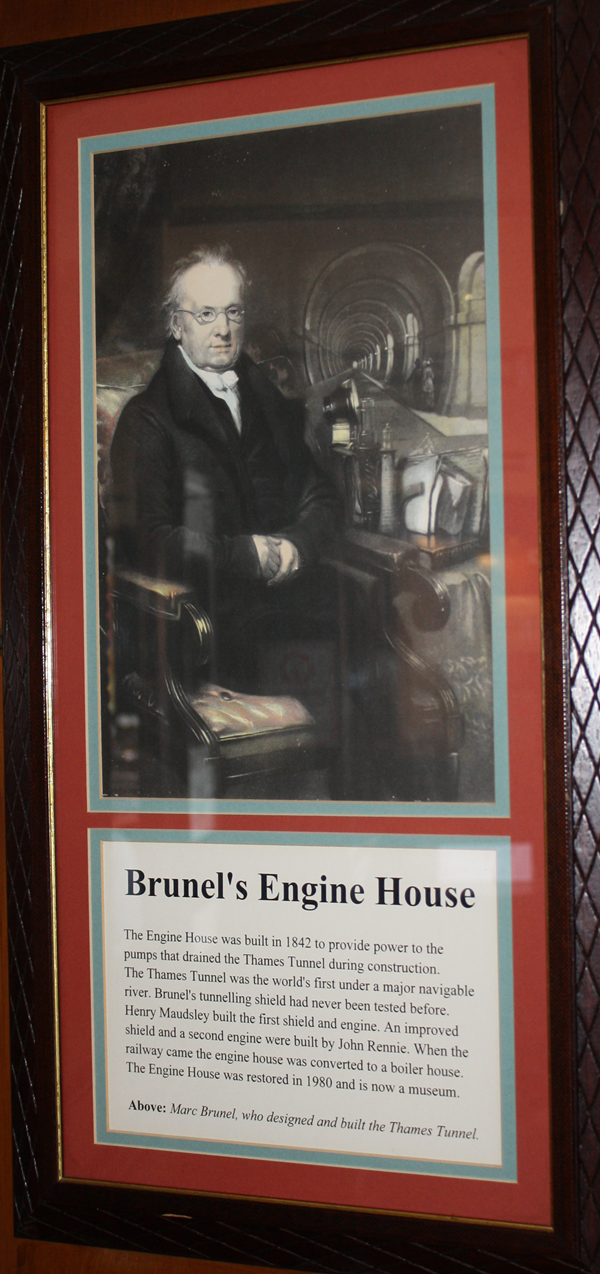

A framed print and text about Marc Brunel’s engine house.

The text reads: The Engine House was built in 1842 to provide power to the pumps that drained the Thames Tunnel during construction. The Thames Tunnel was the world’s first under a major navigable river. Brunel’s tunnelling shield had never been tested before. Henry Maudsley built the first shield and engine. An improved shield and a second engine were built by John Rennie. When the railway came the engine house was converted to a boiler house. The engine house was restored in 1980 and is now a museum.

Above: Marc Brunel, who designed and built the Thames tunnel.

A framed drawing and text about St Helena’s tea gardens.

The text reads: In the summer of 1667 Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, came here by boat from the city. Rotherhithe’s fields and market gardens made it a pleasant and popular place of recreation. He wrote “…with my wife…over to Halfway House (on Lower Road)…and there he drank, and in the cool of the evening back again, and sang with pleasure upon water.”

After the St Helena Tea Gardens opened, just on the other side of Lower Road, in 1770, it attracted the fashionable high society, including the Prince Regent (late George IV) to enjoy the music and dancing.

The gardens stayed open until 1881, becoming in Victorian times a place of popular entertainment.

ST Helena’s was mainly patronised by the local dockers and their families. In the summer there were brass bands and dancing. Singing, acrobatic performances and fireworks “for the delectation of the merry souls of Redriff” added to its allure.

Although very popular locally, St Helena’s never rivalled the gardens at Ranelagh or Vauxhall. It closed down in 1881.

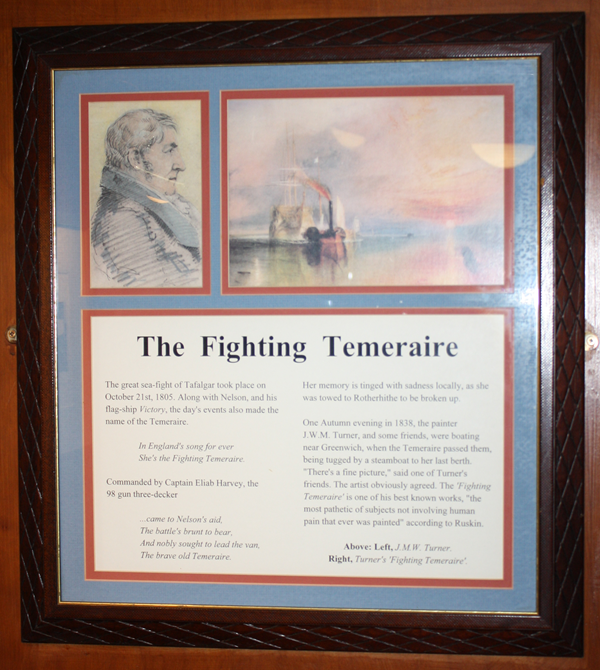

Framed drawings and text about the Temeraire.

The text reads: The great sea-fight of Trafalgar took place on October 21st, 1805. Along with Nelson, and his flag-ship Victory, the day’s events also made name of the Temeraire.

In England’s song for ever

She’s the fighting Temaeraire.

Commanded by Captain Eliab Harvey, the 98 gun three-decker

…came to Nelson’s aid,

The Battle’s burnt to bear,

And nobly sought to lead the van,

The brave old Temeraire.

Her memory is tinged with sadness locally, as she was towed to Rotherhithe to be broken up.

One autumn evening in 1883, the painter J.W.M. Turner, and some friends, were boasting near Greenwich, when the Temeraire passed them, being tugged by steam boat to her last berth. “There’s a fine picture” said one of Turner’s friends. The artist obviously agreed. The ‘fighting Temeraire’ is one of his best known works, “the most pathetic of subjects not involving human pain that was ever painted” according to Ruskin.

Above: left, J.M.W Turner

Right, Turner’s ‘Fighting Temeraire’.

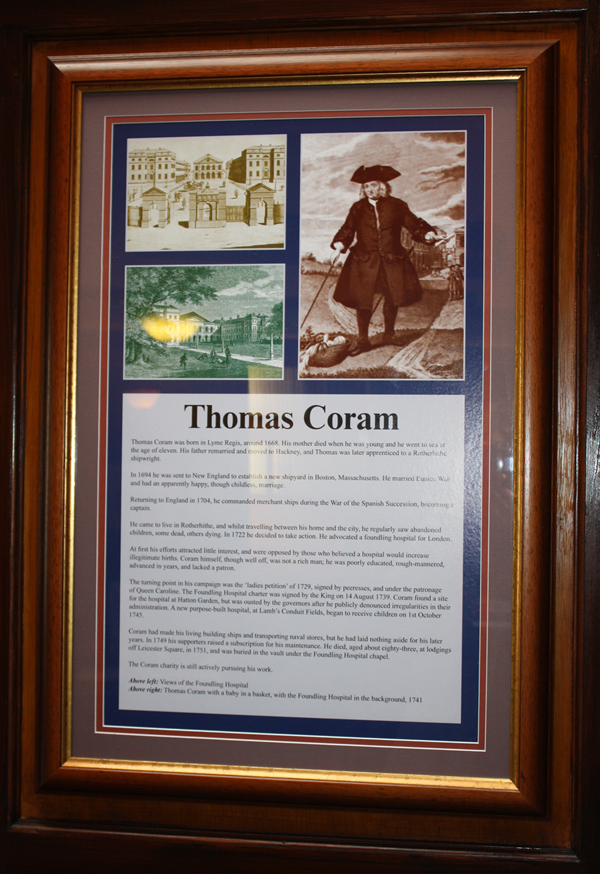

Framed drawings and text about Thomas Coram.

The text reads: Thomas Coram was born in Lyme Regis, around 1668. His mother died when he was young and he went sea at the age of eleven. His father remarried and moved to Hackney, and Thomas was later apprenticed to a Rotherhithe shipwright.

In 1694 he was sent to New England to establish a new shipyard in Boston, Massachusetts. He married Eunice Wail and had an apparently happy, though childless, marriage.

Returning to England in 1704, he commanded merchant ships during the War of the Spanish Succession, becoming a captain.

He came to live in Rotherhithe, and whilst traveling between his home and the city, he regularly saw abandoned children, some dead, others dying. In 1722 he decided to take action. He advocated a founding hospital for London.

At first his efforts attracted little interest, and were opposed by those who believed a hospital would increase illegitimate births. Coram himself, though well off, was not a rich a man; he was poorly educated, rough-mannered, advanced in years, and lacked patron

The turning point in his campaign was the ‘ladies petition’ of 1729, signed by peeresses, and under the patronage of Queen Caroline. The Foundling Hospital Charter was signed by the King on 14 August 1739. Coram found a site for the hospital at Hatton Garden, but was ousted by the governors after he publicly denounced irregularities in their administration. A new purpose-built hospital, at Lamb’s Conduit Fields, began to receive children on 1st October 1745.

Coram had made his living building ships and transporting naval stores, but he laid nothing aside for his later years. In 1749 his supporters raised a subscription for his maintenance. He died aged about eighty- three, at lodgings off Leicester Square, in 1751, and was buried in the vault under the Foundling Hospital Chapel.

The Coram Charity is still actively pursuing his work.

Above left: Views from the Founding Hospital

Above right: Thomas Coram with a baby in a basket, with the foundling Hospital in the background, 1741

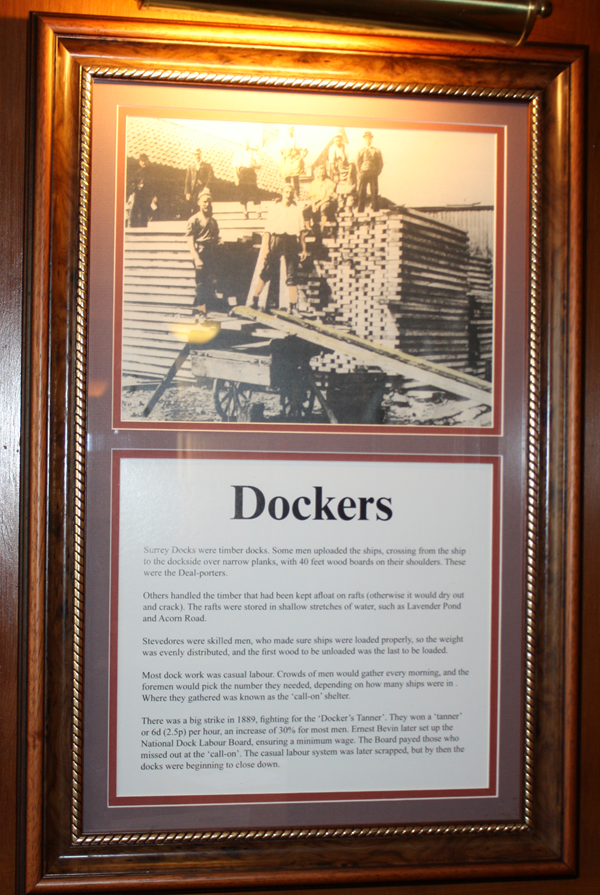

A framed photograph and text about those that worked in Surrey Docks.

The text reads: Surrey Docks were timber dock. Some men uploaded the ships, crossing from the ship to the dockside over narrow planks, with 40 feet wood boards on their shoulders. These were the Deal-porters.

Others handled the timber that had been kept afloat on rafts (otherwise it would dry out and crack). The rafts were stored in shallow stretches of water, such as Lavender Ponds and Acorn Road.

Stevedores were skilled men, who made sure ships were loaded properly, so the weight was evenly distributed, and the first wood to be unloaded was the last to be loaded.

Most dock work was casual labour. Crowds of men would gather every morning, and the foreman would pick the number they needed, depending on how many ships were in. Where they gathered was known as the ‘call-on’ shelter.

There was a big strike in 1889, fighting for the ‘Dockers Tanner’. They won a ‘tanner’ of 6d (2.5p) per hour, an increase of 30% for most men. Ernest Bevin later set up the National Dock Labour Board, ensuring minimum wage. The Board payed those who missed out at the ‘call-on’. The casual labour system was later scrapped, but by then the docks were beginning to close down.

A framed drawing and text about the oldest school in Rotherhithe.

The text reads: The School in Rotherhithe that claimed to be London’s first elementary school, was founded in 1613 by two local men. Peter Hills was an Elizabethan seafarer. Robert Bell we know nothing about. They endowed the original building at the east end of St Mary’s Church in ‘School Lane’, now part of St Mary’s Church Street, “for the education of eight sons of seamen”

This building was demolished in 1795, and the school reopened two years later in Richard Vidlers’ house. The building is still there but is no longer a school. However, its name carries on in the Peter Hills Primary School in Beatson Walk.

A framed print and text about Sir Walter Scott, Sir Walter Besant and Charles Dickens.

The text reads: Charles Dickens in the opening scene of Our Mutual Friend (1865) describes what was a common sight offshore at the lower end of Rotherhithe. A “bird of prey” sits in the waterman’s boat, with the drags out, waiting for bodies of the drowned to float down the tide. Suicides, murder victims or drunks who missed their footing, were common enough to warrant such vigils.

Sir Walter Besant portrays the lower end of Rotherhithe, where the Scandinavian colony had settled, in his story The Captain’s room.

Sir Walter Scott recorded the humour of the Rotherhithe watermen, looking back to the early 1600s, in The fortunes of Nigel. They were well known for what was then called ‘water-wit’. In Scott’s story young Nigel and the plain featured Mistress Martha Trapboi, pass the watermen in a slow-moving boat-

“They were hailed successively as a grocer’s wife upon a party of pleasure with her eldest apprentice, as an old woman carrying her grandson to school, and as a young strapping Irishman conveying an ancient maiden to Dr Rigmarole’s at Redriffe…”

Above: Sir Walter Scott.

A framed print and text about Sir William Maynard Gomm.

The text reads: William Maynard Gomm inherited the Manor of Rotherhithe in 1822. Born in Barbados in 1784 he received his first military commission when he was only ten. He saw action at the Battle of Bergen before he was fifteen. He was at the battle of Waterloo. In 1839 he became commander-in-chief in Jamaica. He found the troops there dying in droves of fever and hangered the authorities in England until they agreed to build a hospital. This achievement he rated above his military exploits.

From 1850-55 he was commander-in-chief in India. Back in England in 1863 he became Colonel of the Coldstream Guards, and in 1868 received the field-marshal’s baton.

He died in 1875, having served in the British Army for 80 years, the longest career on record. His wife, Lady Gomm, died two years later and bequeathed Rotherhithe to her niece, Emily Blanche Carr.

A framed passage about Cuckold’s Point.

The text reads: On the bend of the river, where Limehouse Reach begins, is ‘Cuckolds Point’. The spot was once marked by a tall pole with a pair of horns on top.

The story behind the name goes as follows: King John was hunting on Blackheath, (He was the brother of Richard the Lionheart, and the ‘baddie’ in most stories, including Robin Hood. Richard forgave him on his deathbed and named him his successor. He is best remembered for signing the Magna Carter).

Feeling weary King John entered a miller’s cottage at Charlton Village.

Only the miller’s wife was at home, a young and beautiful girl. This was better refreshment than he had hoped for. He was handsome, he was sweet-talking, and he was king. Seduction is easy.

But just as the King kissed her the miller returned. He recognised his wife’s lover just in time, to avoid creating a job vacancy at the highest level. The King, provided the miller forgave his wife, agreed to give him all the land from Charlton to the point at Rotherhithe.

The river boundary of his property was ever after called ‘Cuckolds point’. The miller was also granted an annual fair on 18 October, which was called the Horn Fair.

A framed print and text about Samuel Gillam.

The text reads: Samuel Gillam was very well known in the mid-18th century. He was born in Rotherhithe in 1772. His father was a captain in the East India Company. His mother, Ann Hunt, came from an old Rotherhithe family.

Gillam became a surgeon in Rotherhithe. In 1745 his support of the government led to him being made JP. In 1768, Gillam, along with two other Justices, had to confront the riotous mob that gathered outside the King’s Bench prison, where John Wilkes, the radical politician, was being held.

The Riot Act was read. Gillam stepped forward and spoke, persuading the mob to return to their homes. He was interrupted by a tone hitting him on the head, which made him reel backwards. Gillam yelled to the soldiers to fire on the crowd. The resulting mayhem left one man dead. Gillam was tried as the Old Bailey and acquitted, without a single witness being called.

Gillam died at his house in Paradise Street in 1793.

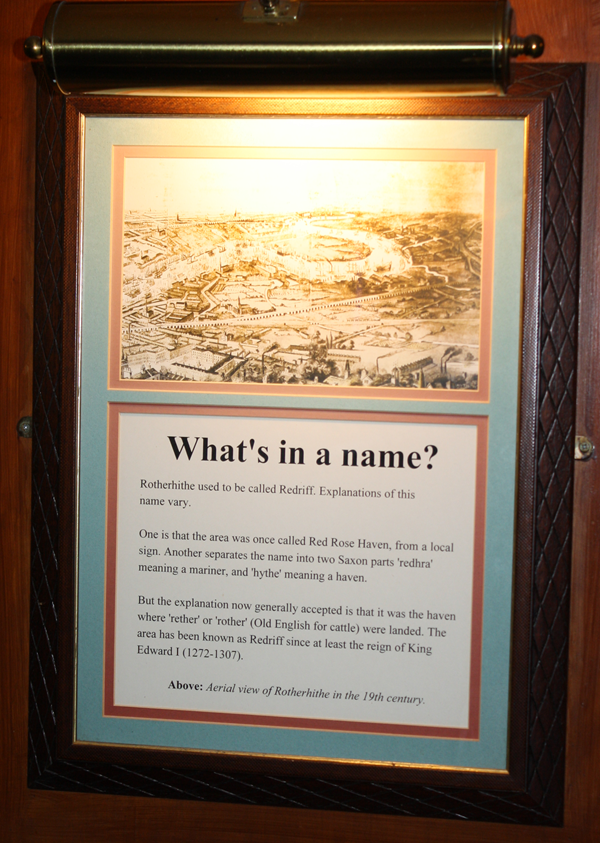

A framed drawing and text about Rotherhithe.

The text reads: Rotherhithe used to be called Redriff. Explanations of this name vary.

One is that the area was once called Red Rose Haven, from the local sign. Another separates the name onto two saxon parts ‘redhra’ meaning mariner, and ‘hythe’ meaning a haven.

But the explanation now generally accepted is that it was haven where ‘rether’ or ‘rother’ (old English for cattle) were landed. The area has been known as Redriff since at least the reign of King Edward I (1272-1307).

Above: Aerial view of Rotherhithe in the 19th century.

A framed photograph of Central Granary, Millwall Docks c.1920.

A framed photograph of Surrey Docks.

Framed photographs of Surrey Docks 1843, planks being unloaded 1930 and Heinkel bomber over Surrey Docks 7th September 1940.

A framed photograph of Rotherhithe c.1905.

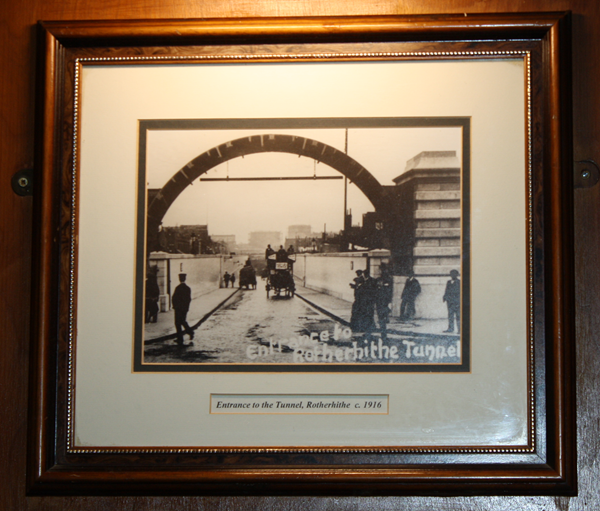

A framed photograph of the entrance to the Tunnel, Rotherhithe c.1916.

A framed photograph of a Billingsgate porter c.1920.

A framed photograph of Southwark Park, Rotherhithe c.1907.

A framed photograph of the bridge in Redriff Road where dockers and stevedores were called on.

This picture was provided by the late Jim Hitch, a local to Surrey Docks.

An original binnacle, now on display in the pub.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.