Pub history

The Moon Under Water

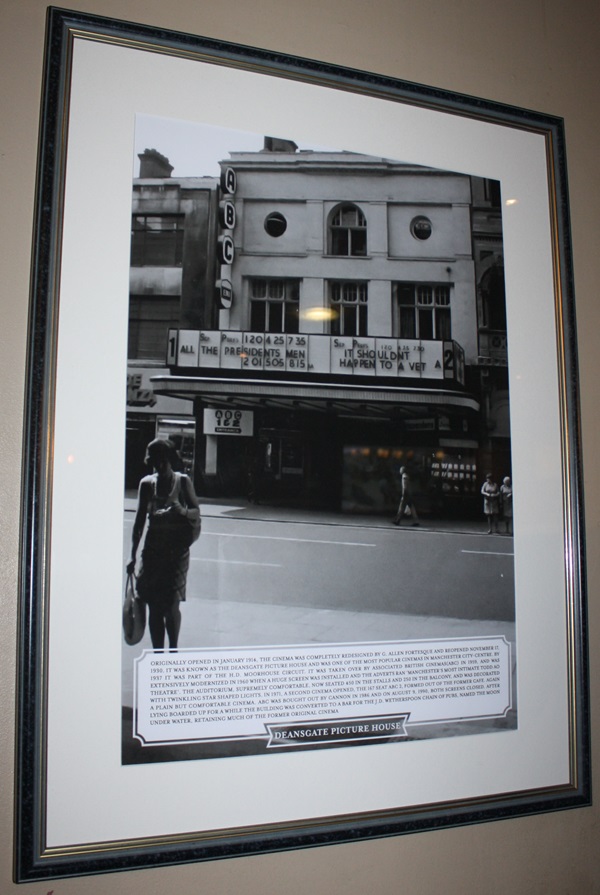

Originally opening in January 1914, the cinema was completely redesigned by G Allen Fortesque and reopened in November 1930. It was known as the Deansgate Picture House. By 1960, the auditorium was supremely comfortable, seating 450 (stalls) and 250 (balcony), decorated with twinkling star-shaped lights. After lying boarded up for a while, the building was converted and named The Moon Under Water, retaining much of the former original cinema.

68–74 Deansgate, Manchester, M3 2FN

Originally opening in January 1914, the cinema was completely redesigned by G Allen Fortesque and reopened in November 1930. It was known as the Deansgate Picture House. By 1960, the auditorium was supremely comfortable, seating 450 (stalls) and 250 (balcony), decorated with twinkling star-shaped lights. After lying boarded up for a while, the building was converted and named The Moon Under Water, retaining much of the former original cinema.

A framed photograph of Deansgate Picture House.

The text reads: Originally opening in January 1914, the cinema was completely redesigned by G. Allen Fortesque and reopened November 17, 1930. It was known as the Deansgate Picture House and was one of the most popular cinemas in Manchester city-centre. By 1937 it was part of the H.D. Moorhouse Circuit, it was taken over by associated British Cinemas (ABC) in 1959, and was extensively modernized in 1960 when a huge screen was installed and the adverts ran ‘Manchester’s Most Intimate Todd AO Theatre’. The auditorium, supremely comfortable, now seated 450 in the stalls and 250 in the balcony, and was decorated with twinkling star shaped lights. In 1971, a second cinema opened, the 167 seat ABC 2, formed out of the former café. Again a plain but comfortable cinema. ABC was bought out by Cannon in 1986 and on August 9, 1990, both screens closed. After lying boarded up for a while the building was converted to a bar for the J.D. Wetherspoon chain of pubs, named The Moon Under Water, retaining much of the former original cinema.

Framed photographs of The Deansgate Picture House during its last week open.

This sculpture is an old steam generator.

It was used in the Deansgate Picture House.

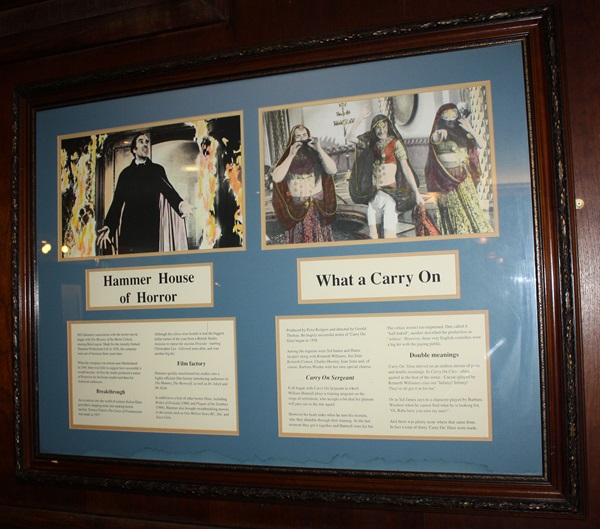

Framed photographs and text about Will Hammer’s horror films and the Carry On films.

The text reads: Hammer House of Horror

Will Hammer’s association with horror movies began with The Mystery of the Marie Celeste starring Bela Lugosi. Made for the recently formed ‘Hammer Productions Ltd’ in 1936, the company went out of business three years later.

When the company was reborn near Maidenhead in 1949, there was little to suggest how successful it would become. At first the studio produced a series of B movies for the home market and then for American audiences.

An excursion into the world of science-fiction films provided a stepping stone into making horror movies. Terence Fisher’s The Curse of Frankenstein was made in 1957.

Although the critics were hostile it was the biggest dollar earner of the year from a British Studio. Anxious to repeat the success Dracula – starring Christopher Lee – followed soon after, and was another big hit.

Hammer quickly transformed his studios into a highly efficient film factory introducing audiences to The Mummy, The Werewolf, as well as Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

In addition to a host of other horror films, including Brides of Dracula (1960) and Plague of the Zombies (1966), Hammer also brought swashbuckling movies to the screen such as One Million Years BC, She, and Slave Girls.

What a Carry On

Produced by Peter Rodgers and directed by Gerald Thomas, the hugely successful series of ‘Carry On’ films began in 1958.

Among the regulars were Sid James and Hattie Jacques along with Kenneth Williams, Jim Dale, Kenneth Connor, Charles Hawtry, Joan Sims and, of course, Barbara Windsor with her own special charms.

It all began with Carry On Sergeant in which William Hartnell plays a training sergeant on the verge of retirement, who accepts a bet that his platoon was pass out as the star squad.

However his heart sinks when he sees his recruits, who then shamble through their training. At the last moment they get it together and Hartnell wins his bet.

The critics weren’t too impressed. One called it “half-baked”, another described the production as “witless”. However, these very English comedies were a big hit with the paying public.

‘Carry On’ films thrived on an endless stream of puns and double meanings. In Carry On Cleo – often quoted as the best series – Caesar (played by Kenneth Williams) cried out “Infamy! Infamy! They’ve all got it in for me”.

Or as Sid James says to a character played by Barbara Windsor when he cannot find what he is looking for, “Oi, Babs have you seen my nuts?”.

And there was plenty more where that came from. In fact a total of thirty ‘Carry On’ films were made.

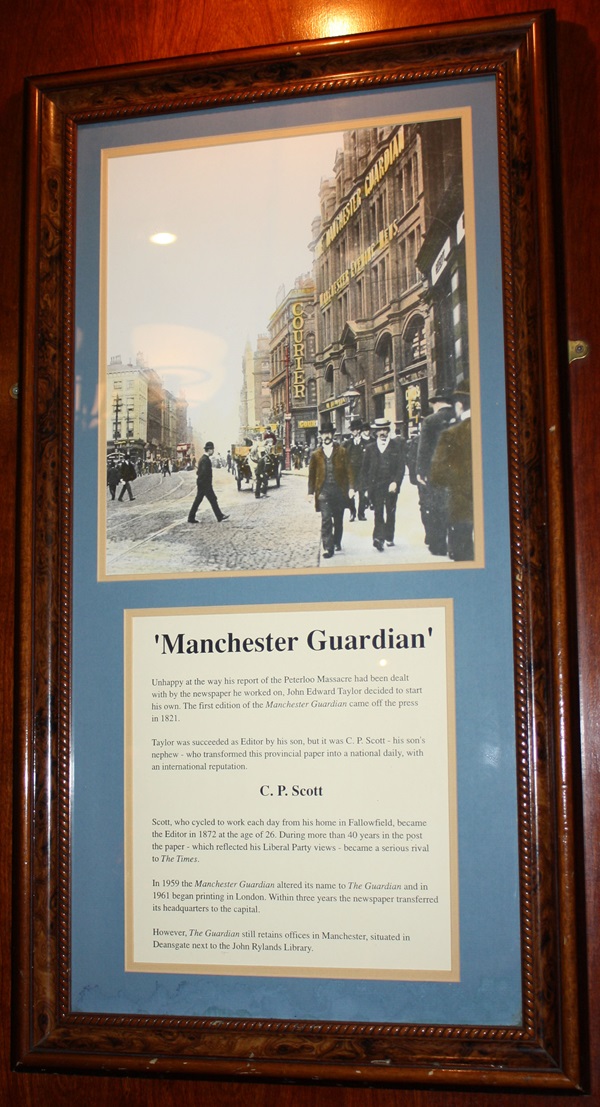

A framed photograph and text about the Manchester Guardian.

The text reads: Unhappy at the way his report of the Peterloo Massacre had been dealt with by the newspaper he worked on, John Edward Taylor decided to start his own. The first edition of the Manchester Guardian came off the press in 1821.

Taylor was succeeded as Editor by his son, but it was C. P. Scott – his son’s nephew – who transformed this provincial paper into a national, daily, with an international reputation.

Scott, who cycled to work each day from his home in Fallowfield, became the Editor in 1872 at the age of 26.during more than 40 years in the post the paper – which reflected his Liberal Party views – became a serious rival to The Times.

In 1959 the Manchester Guardian altered its name to The Guardian and in 1961 began printing in London. Within three years the newspaper transferred its headquarters to the capital.

However, The Guardian still retains offices in Manchester, situated in Deansgate next to the John Rylands Library.

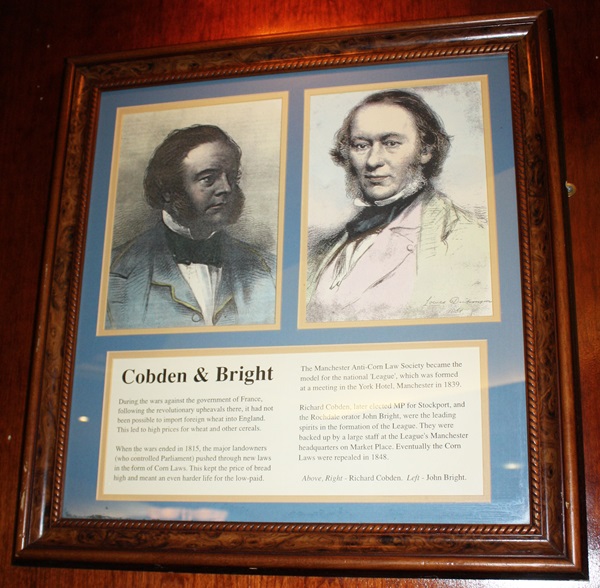

Framed drawings and text about Corn Laws.

The text reads: During the wars against the government of France, following the revolutionary upheavals there, it had not been possible to import foreign wheat into England. This led to high prices for wheat and other cereals.

When the wars ended in 1815, the major landowners (who controlled Parliament) pushed through new laws in the form of Corn Laws. This kept the price of bread high and meant an even harder life for the low-paid.

The Manchester Anti-Corn Law Society became the model for the national ‘League’, which was formed at a meeting in the York Hotel, Manchester in 1839.

Richard Cobden, later elected MP for Stockport, and the Rochdale orator John Bright, were the leading spirits in the formation of the League. They were backed up by a large staff at the League’s Manchester headquarters on Market Place. Eventually the Corn Laws were repealed in 1848.

Above, Right – Richard Cobden. Left – John Bright.

A framed old photograph of JL Levy Tailors.

A framed old photograph of Deansgate, Manchester.

A framed old photograph of the streets of Manchester.

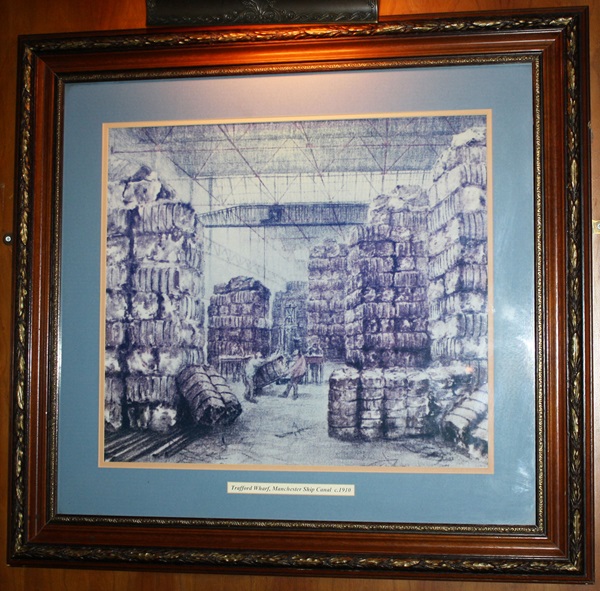

A framed drawing of Trafford Wharf, Manchester Ship Canal c.1910.

A framed photograph of Piccadilly and Market Street c.1910.

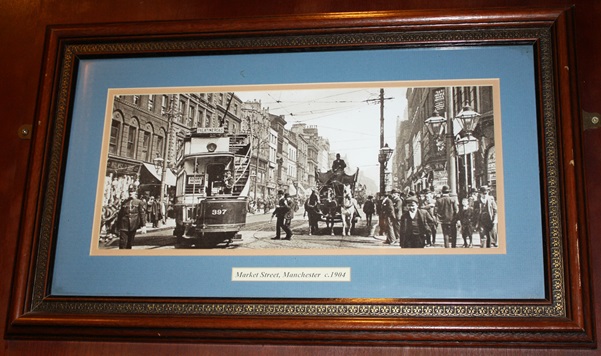

A framed photograph of Market Street, Manchester c.1904.

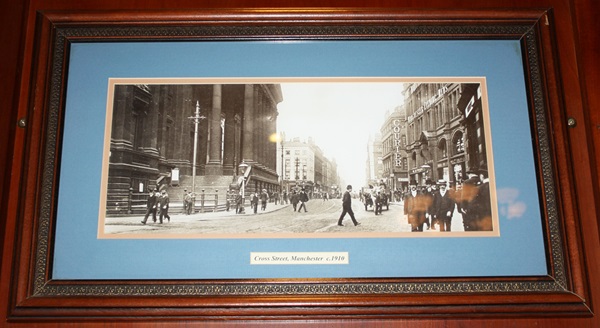

A framed photograph of Cross Street, Manchester c.1910.

A framed photograph of Cromwell’s Monument, Manchester c.1906.

A framed photograph of the free trade hall, Manchester c.1912.

A framed photograph of the Royal Exchange, Manchester c.1910.

A framed photograph of the fire station, Manchester c.1912.

Internal photographs of some original design features and layout. These are from when the building used to be the Deansgate Picture House.

External photograph of the building – front.

The original picture house’s brickwork can be seen above the pub’s sign.

External photograph of the building – side entrance.