Pub history

The Roebuck Inn

Discover the history of the famous Nottingham Castle.

Almost opposite this Wetherspoon pub is the former Malt Cross Music Hall. Built in 1877, the music hall occupied the site of the Malt Cross public house, originally The Roebuck, first recorded in 1760.

Prints and text about The Roebuck Inn

The text reads: This J D Wetherspoon pub is named after an inn which once stood opposite. An alehouse from 1760, the Roebuck was later renamed the Malt Cross. It was rebuilt in 1877 as the Malt Cross Music Hall by Charles Weldon. The architect, Edwin Hill, built a four-storey wing at right-angles to the street, with a glazed roof held up by arches made from strips of wood glued together.

The music hall opened with the announcement that ‘the Alhambra Band has been engaged to play all the popular music of the day’. The Alhambra was another music hall owned by Mr Weldon. Admission was free, profits coming from the food and drink.

A later owner, Lewis Donkersley, performed in other music halls as ‘Alec Lewis, Operatic Comedian’. The music hall was closed in 1914. After a period as a warehouse, the Malt Cross was briefly a pub again in the 1980s. More recently, it has again provided musical entertainment, and been used as the Potter’s House, a Christian charity.

Above, left: Advert for the Malt Cross

Right: Vesta Tilley – the famous male impersonator who made her music hall debut in Nottingham, in 1868

Prints and text about St James’ Street

The text reads: The street in which this J D Wetherspoon pub stands is named after one of the city’s oldest places of worship, first mentioned in 1265.

However, St James’ Chapel, which stood between this street and Friar Lane, may well date from Saxon times. The building also gave its name to nearby Chapel Bar (one of the city gates), and to Moothallgate, as Friar Lane was once known. It was originally the chapel of Red Hall, later owned by William Peverel, lord of the manor and an illegitimate son of William the Conqueror. When he moved to Nottingham Castle, the chapel became a courthouse or moot hall.

The building was later in the possession of Lenton Priory, but then passed to the Carmelites, who had built a friary near here in 1272. Services at the friary were attended by Henry VIII in 1511. His services adviser, Cardinal Wolsey, was a later guest.

The friary was one of the monasteries Henry closed down, and was rebuilt as a town house, known as Dorothy Vernon’s House. The house was demolished in 1927 as part of the widening of Friar Lane.

Left: The friary

Above, left: Old Peveril, a debtors’ prison

Above, right: Cardinal Wolsey

Right: Dorothy Vernon’s House

Prints and text about Maid Marian

The text reads: Since the late 1950s, St James’ Street (on which this J D Wetherspoon pub stands) has been cut in two by Maid Marian Way. The new dual carriageway was named after Robin Hood’s famous companion.

Robin and Marian are said to have been married in Edwinstowe Church, at the heart of Sherwood Forest. However, a plaque near Robin’s statue on Castle Green, Nottingham, shows their hands being joined by Richard I, who stands under a tree.

Stories and ballads featuring Robin Hood have circulated for many centuries. The earliest surviving written reference dates from the 14th century, and implies that the character was already well-known.

However, the character of Maid Marian first appears in association with Robin Hood some 200 years later.

They probably became connected as a result of both featuring in the old May Day celebrations.

Robin Hood plays were often performed on May Day, while Maid Marian (usually played by a man) was a figure in the May Games and morris dances. She sometimes appeared as Queen of the May herself.

Top, left: Maid Marian

Top, right: Robin Hood turns butcher to sell meat in Nottingham

Above: Robin Hood and Little John

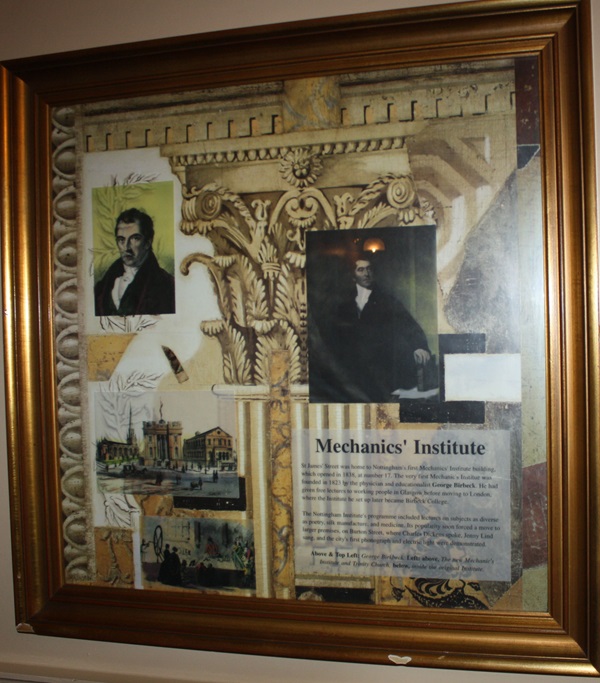

Prints and text about the Mechanics’ Institute

The text reads: St James Street was home to Nottingham’s first Mechanics’ Institute building, which opened in 1838, at number 17. The very first Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1823 by the physician and educationalist George Birbeck. He had given free lectures to working people in Glasgow before moving to London, where the institute he set up later became Birbeck College.

The Nottingham institute’s programme included lectures on subjects as diverse as poetry, silk manufacture and medicine. Its popularity soon forced a move to larger premises, on Burton Street, where Charles Dickens spoke, Jenny Lind sang, and the city’s first phonograph and electric light were demonstrated.

Above, top-left: George Birkbeck

Left, above: The new Mechanics’ Institute and Trinity Church

Left, below: Inside the original institute

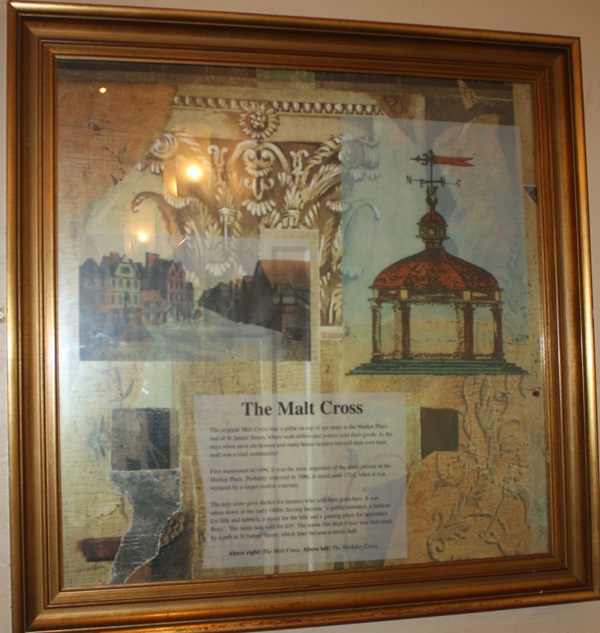

Prints and text about the Malt Cross

The text reads: The original Malt Cross was a pillar on top of 10 steps at the Market Place end of St James’ Street, where malt-sellers and potters sold their goods. In the days when most alehouses and many householders brewed their own beer malt, was a vital commodity!

First mentioned in 1496, it was the most important of the three crosses in the Market Place. Probably renewed in 1686, it stood until 1714, when it was replaced by a larger roofed structure.

The new cross gave shelter for farmers who sold their grain here. It was taken down in the early 1800s, having become ‘a public nuisance, a harbour for filth and rubbish, a resort for the Idle and a gaming place for apprentice Boys’. The stone was sold for £45. The name The Malt Cross was later used by a pub in St James’ Street, which later became a music hall.

Above, right: The Malt Cross

Above, left: The Weekday Cross

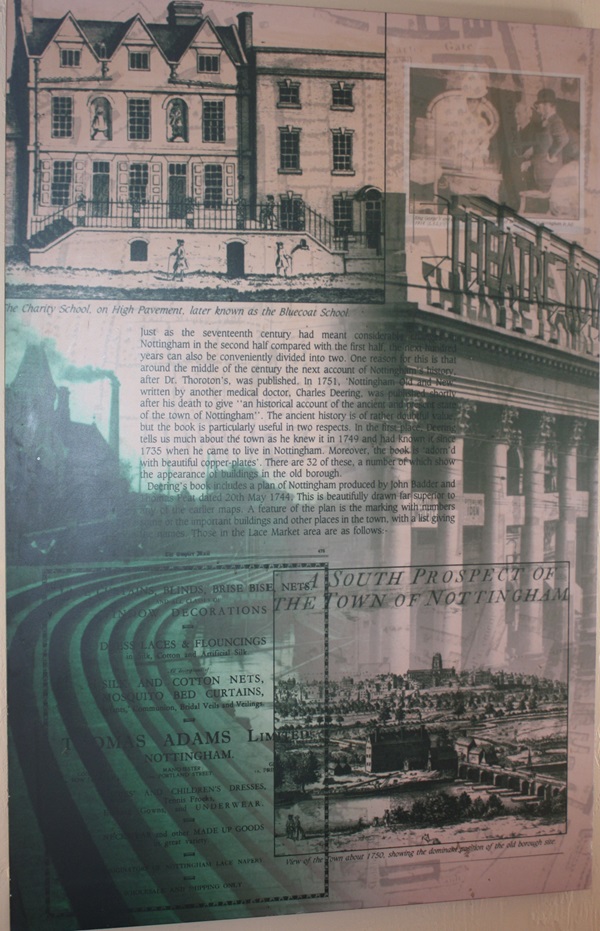

Prints, photographs and text about the history of Nottingham

The text reads: Although there is little evidence of what the old borough looked like in medieval times, no doubt most of the houses would have been fairly modest ones, probably made of timber or timber-framed with wattle and daub. Some idea of their appearance, and that of the rest of the town, can be obtained from an early map of the town, created by John Speed in 1610. This shows the street layout, and a pictorial representation of the houses on each street is given. It appears that in the Lace Market area the houses stretched along both side of the streets between Fletcher Gate and Stoney Street, with open space or gardens at the rear. A rather clearer and more detailed map was that published in 1677 in Dr Robert Thoroton’s book The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire. This map shows that there was little difference in the area since 1610.

The first half of the 17th century in England was not a particularly prosperous time, with the political and religious differences of the Stuart period culminating in the Civil Wars and the temporary abolition of the monarchy. Nottingham shared in the troubles this caused. lt had been thriving in the two centuries preceding this time, as witnessed by the completion of St Mary’s Church in the 15th century. This was made possible by the wealth created by the wool trade and the benefactions of a number of prosperous merchants such as Thomas Thurland. By the early part of the 17th century, this trade had been superseded by cloth-making in parts of the country. The castle too had ceased to have royal status, and the building itself was decaying. The disruption caused by the Civil Wars could not have helped Nottingham’s economy.

Just as the 17th century had meant considerable changes in Nottingham in the second half compared with the first half, the next 100 years can also be conveniently divided into two. One reason for this is that around the middle of the century, the next account of Nottingham’s history, after Dr Thoroton’s, was published. In 1751, Nottingham Old and New, written by another medical doctor, Charles Deering, was published shortly after his death to give ‘an historical account of the ancient and present state of the town of Nottingham’. The ancient history is of rather doubtful value, but the book is particularly useful in two respects. In the first place, Deering has written about the town as he knew it in 1749 and had known it since 1736 when he came to live in Nottingham. Moreover, the book is ‘adorned with beautiful copper plates’. There are 32 of these, a number which show the appearance of buildings in the old borough.

Deering’s book included a plan of Nottingham produced by John Badder and Thomas Peat, dated 20 May 1744. This is beautifully drawn, far superior to any of the earlier maps. A feature of the plan is the marking with numbers some of the most important building and other places in the town, with a list giving the names.

Prints of Nottingham

Left: Wesley Church, Chillwell Road, c1905

Middle: Post Office Square from High Road, c1905

Bottom, right: High Road from the Square

Top, right: The Parish Church of St John the Baptist, c1902

Photographs and text about Nottingham Castle

The text reads: Nottingham Castle is a castle in Nottingham, England. It is located in a commanding position on a natural promontory known as “Castle Rock”, with cliffs 130 feet (40m high) to the south and west. In the middle ages, it was a major royal fortress and occasional royal residence. In decline by the 16th century, it was largely demolished in 1649, with the Duke of Newcastle later building a mansion on the site. This was burnt out by rioters in 1831 and left as a ruined shell by the Duke, later being adapted to create an art gallery and museum, which the building is still used as today. Little of the original castle survives, but sufficient portions remain to give an impression of the layout of the site.

Photographs and text about Raleigh Bicycle Company

The text reads: The Raleigh Bicycle Company is a bicycle manufacturer originally based in Nottingham, UK. Founded by Woodhead and Angois in 1885, who used Raleigh as their brand name, it is one of the oldest bicycle companies in the world. It became The Raleigh Cycle Company in December 1888, which was a registered limited liability company in January 1889. From 1921 to 1935, Raleigh also produced motorcycles and three-wheeled cars leading to the formation of the Reliant company. The history of Raleigh Bicycles started in 1885, when Richard Morris Woodhead from Sherwood Forest, and Paul Eugene Louis Angois, a French citizen, set up a small bicycle workshop in Raleigh Street, Nottingham. In the spring of that year, they started advertising in the local press. The Nottinghamshire Guardian of 15 May 1885 printed what was possibly the first Woodhead and Angois classified advertisement. Nearly two years later, the 11 April 1887 issue of the Nottingham Evening Post contained a display advertisement for the Raleigh ‘Safety’ model under the banner ‘Woodhead, Angois and Ellis Russel Street Cycle Works’. William Ellis had recently joined the partnership and provided much-needed financial investment. Like Woodhead and Angois, Ellis’ background was in the lace industry. He was a lace gasser, a service provider involved in the bleaching and treating of lace, with premises in nearby Clare Street and Glasshouse street. Thanks to Ellis, the bicycle works had now expanded round the corner from Raleigh Street into former laceworks on the adjoining road, Russel street. By 1888, the company was making about three cycles a week and employed around half a dozen men. It was one of 15 bicycle manufacturers based in Nottingham at the time.

An illustration of Nottingham Castle

External photograph of the building – main entrance