Pub history

The Francis Newton

Broombank House was built for the wealthy cutlery manufacturer Francis Newton, as his family home. The Georgian-style house was within easy walking or riding distance of his Portobello Works. In 1844, Newton was elected Master Cutler, the head of the prestigious Company of Cutlers. Sheffield is the cutlery capital of the world.

Broombank House was built for the wealthy cutlery manufacturer Francis Newton, as his family home. The Georgian-style house was within easy walking or riding distance of his Portobello Works. In 1844, Newton was elected Master Cutler, the head of the prestigious Company of Cutlers. Sheffield is the cutlery capital of the world.

A plaque documenting the history of The Francis Newton building

The text reads: This building is the former Broombank House, which was built in the 1820s for the wealthy cutlery manufacturer, Francis Newton, for whom this pub is named. In 1844, Newton was elected Master Cutler, the head of the prestigious Company of Cutlers. Sheffield is the cutlery capital of the world.

The premises were refurbished by J D Wetherspoon in February 2010.

Framed photographs and text about The Francis Newton

The text reads: Francis Newton was a successful cutlery manufacturer in Sheffield. He had a large works nearby at Portobello.

The Georgian-style building that you are now in is the former Broombank House that was built in the 1820s as his family home. Much of the Victorian garden around Broombank House lay untouched for many years. It is now Lynwood Gardens, an oasis of ‘mature woodland and open glades’ on the edge of Sheffield city centre.

In 1844, Newton was elected Master Cutler, head of the prestigious Company of Cutlers, established in 1624. The role of the Master Cutler is to act as an ambassador of industry for Sheffield. A new incumbent is chosen each year by the freemen of the company; however, several tenures have been longer, including those of Sir John Brown, Mark Firth and William Henry Ellis.

Far left: Francis Newton

Left: Plaque in Cutlers’ Hall

Above: Mark Firth

Top, right: Fredrick Mappin, Master Cutler, 1855

Right: William Henry Ellis

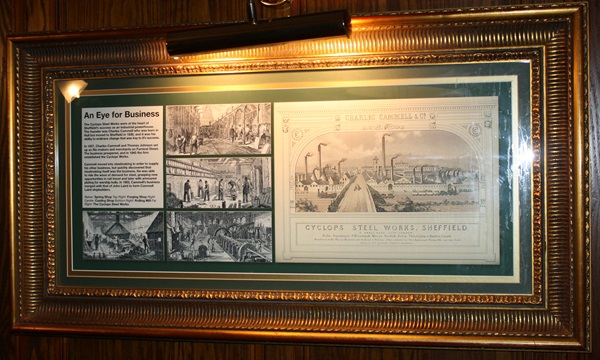

Framed drawings and text about the Cyclops Steel Works

The text reads: The Cyclops Steel Works were at the heart of Sheffield’s success as an industrial powerhouse. The founder was Charles Cammell, who was born in Hull but moved to Sheffield in 1830, and it was his ability to embrace change that was key to its success.

In 1837, Charles Cammell and Thomas Johnson set up as file-makers and merchants on Furnival Street. The business prospered, and in 1845 the firm established the Cyclops Works.

Cammell moved into steelmaking in order to supply his other business but quickly discovered that steelmaking itself was the business. He was able to ride the wave of demand for steel, grasping new opportunities in rail travel and later with armoured plating for warship hulls. In 1903, Cammell’s business merged with that of John Laird to form Cammell Laird shipbuilders.

Below: Spring shop

Right, top: Forging shop

Right, centre: Casting shop

Right, bottom: Rolling mill

Far right: The Cyclops Steel Works

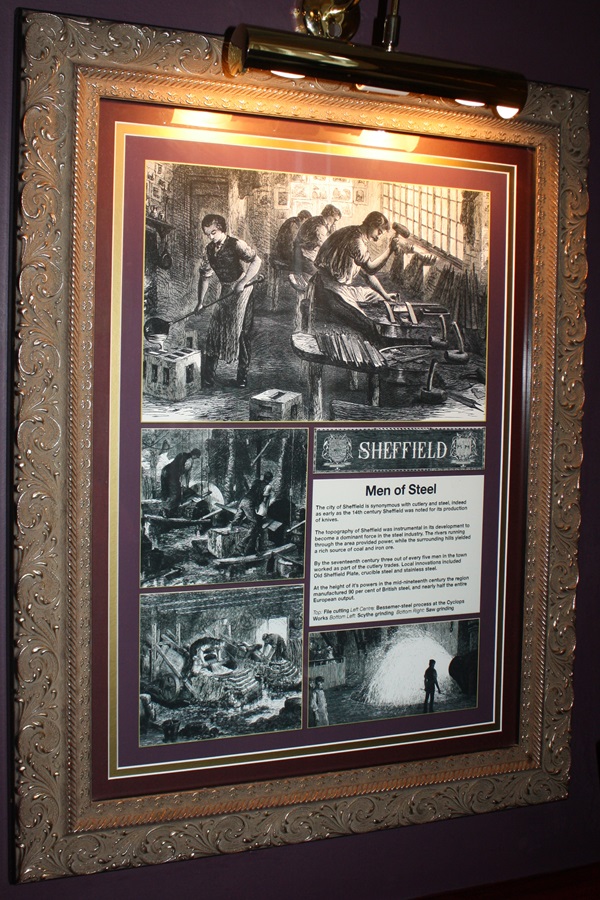

Framed drawings and text about the steel industry

The text reads: The city of Sheffield is synonymous with cutlery and steel. Indeed, as early as the 14th century, Sheffield was noted for its production of knives.

The topography of Sheffield was instrumental in its development to become a dominant force in the steel industry. The rivers running through the area provided power, while the surrounding hills yielded a rich source of coal and iron ore.

By the 17th century, three out of every five men in the town worked as part of the cutlery trades. Local innovations included Old Sheffield Plate, crucible steel and stainless steel.

At the height of its powers in the mid-19th century, the region manufactured 90 per cent of British steel, and nearly half the entire European output.

Top: File cutting

Left, centre: Bessemer-steel processing at the Cyclops Works

Bottom, left: Scythe-grinding

Bottom, right: Saw-grinding

Framed photographs and text about men and women who worked in the Sheffield steel industry during the First World War and some of the machines they worked on

The text reads: The unswerving endeavour of the men and women who worked in the Sheffield Steel Industry during both World Wars ensured that the frontline troops received the vital supplies needed to fight for our freedom.

Despite contending with air raids, rationing and great family upheavals, the Sheffield steel machine continued to churn out the tools of war.

The foundries, large and small, that defined the landscape, cast gun barrels and turrets, shell and bomb castings, aircraft components and engine parts. The rolling mills produced armoured plating and ‘tin’ helmets.

Framed drawings, photographs and text about theatres in Sheffield

The text reads: The Crucible Theatre in Sheffield is a household name, due to its staging of the World Snooker Championships. However, if history had been kinder, Sheffield would have been able to boast several more truly wonderful venues.

First to suffer the cruel hand of fate was The Surrey Music Hall, which was built in 1851 and was demolished after a fire in 1865.

Then, in quick succession, flames took The Theatre Royal in 1936 and then just a year later, in 1937, the Albert Hall also perished.

The Empire, on Charles Street, didn’t fare much better. It was a huge theatre with over 2,000 seats, which was struck by fire and a direct hit by the Luftwaffe, but still it survived until 1959.

Right: The Surrey Music Hall

Below: The Albert Hall

Bottom, left: The Empire

Bottom, centre: Programme, 1911

Below, centre right: Theatre Royal Ticket

Bottom, right: A seating plan of The Theatre Royal

Framed photographs, drawings and text about Broomhill

The text reads: In the mid-18th century, Broomhill was an area of rugged moorland. These rural heights were used as the Crookesmoor Racecourse from 1711 to 1781. There were a few houses and a huddle of cottages to the east of the present Botanical Gardens, including an inn ‘The Ball in the Tree’, demolished in 1870.

The suburb that developed here took its name from the house built by William Newbould in 1792, which he called ‘Broomhill’. Broomhill then became a place sought after by wealthy industrialists and the well-to-do.

The Mount was built in 1830–32 by local architect William Flockton, who also designed the similar but grander Wesley College six years later. The Mount emulated the Royal Crescent in Bath by containing several dwellings within what looked like a country mansion. It became a fashionable location. The most famous resident was the editor and poet James Montgomery, who lived here from 1835 until his death in 1854.

Montgomery settled in Sheffield in 1792 as clerk on the Sheffield Register newspaper. In 1794, he launched and edited the Sheffield Iris. He was jailed twice for his paper’s political articles.

Top, left: A painting of James Montgomery

Top, right: The ‘Ball in the Tree’ inn

Above, right: The poet and resident at The Mount, James Montgomery

Left: The Mount, c1835

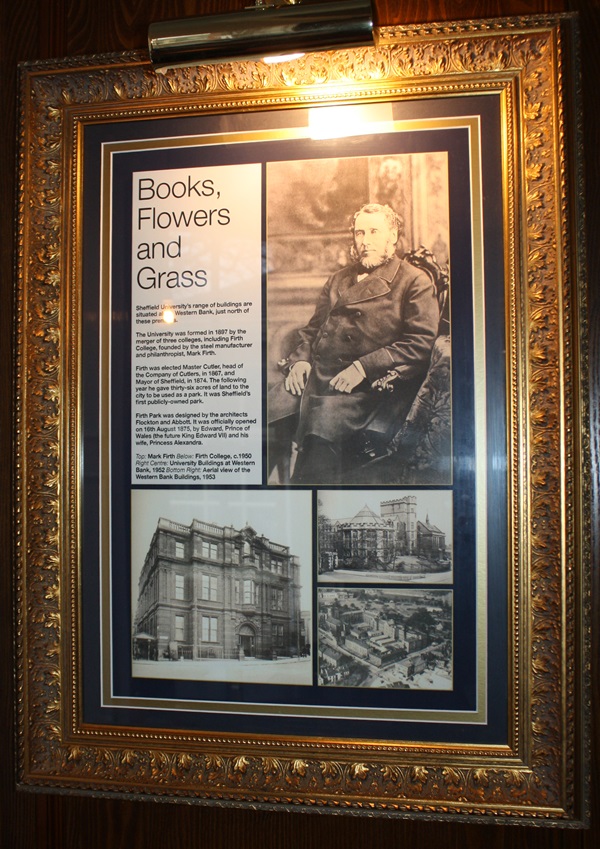

Framed photographs and text about Sheffield University

The text reads: Sheffield University’s range of buildings are situated along Western Bank, just north of these premises.

The university was formed in 1897 by the manager of three colleges, including Firth College, founded by the steel manufacturer and philanthropist Mark Firth.

Firth was elected Master Cutler, head of the Company of Cutlers, in 1867, and Mayor of Sheffield in 1874. The following year, he gave 36 acres of land to the city to be used as a park. It was Sheffield’s first publicly owned park.

Firth Park was designed by the architects Flockton and Abbott. It was officially opened on 16 August 1875, by Edward, Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII) and his wife, Princess Alexandra.

Top: Mark Firth

Below: Firth College, c1950

Right, centre: University buildings at Western Bank, 1952

Bottom, right: Aerial view of the Western Bank buildings in 1953

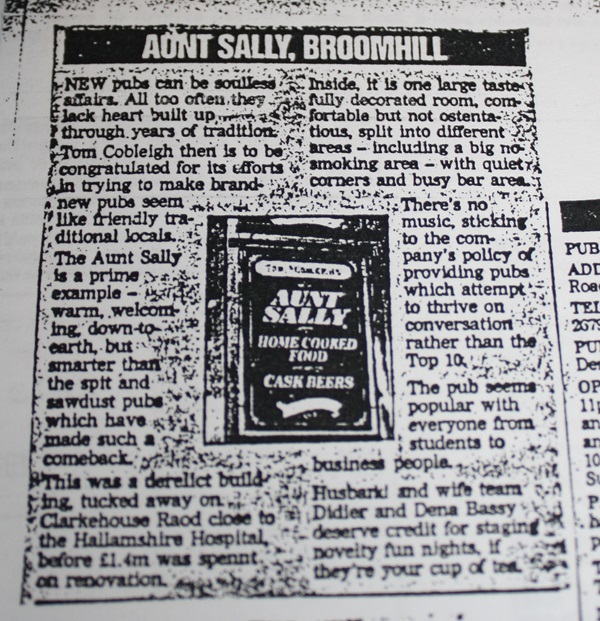

An article about this pub opening in March 1995 as the Aunt Sally

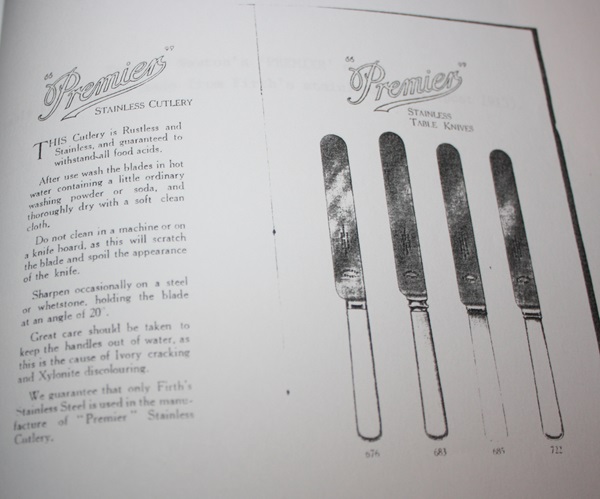

An advert for Premier stainless cutlery

A framed painting entitled Storm Sky Light, Tinsley Towers, by Mark H Wilson

‘The last few rays of sunlight, before the storm descends, reflect on cars and buildings, and silhouette Sheffield’s landmark cooling towers looking toward the city centre.’

External photograph of the building – main entrance