Pub history

The Tilley Stone

Tyneside and coal were linked for centuries, with mines in and around Gateshead. The ‘Five Quarter’ seam was worked at the Derwent and Gateshead Fell pits and the ‘Three Quarter’ at Dunston Colliery, along with the ‘Tilley’ and ‘Stone’ seams. Dunston’s wooden staithes were built in 1893 for loading coal onto ships, continuing in use until the 1970s. Now restored and a listed monument, they form reputedly the largest wooden structure in Europe – a reminder of the busy days of the ‘Coaly Tyne’.

Tyneside and coal were linked for centuries, with mines in and around Gateshead. The ‘Five Quarter’ seam was worked at the Derwent and Gateshead Fell pits and the ‘Three Quarter’ at Dunston Colliery, along with the ‘Tilley’ and ‘Stone’ seams. Dunston’s wooden staithes were built in 1893 for loading coal onto ships, continuing in use until the 1970s. Now restored and a listed monument, they form reputedly the largest wooden structure in Europe – a reminder of the busy days of the ‘Coaly Tyne’.

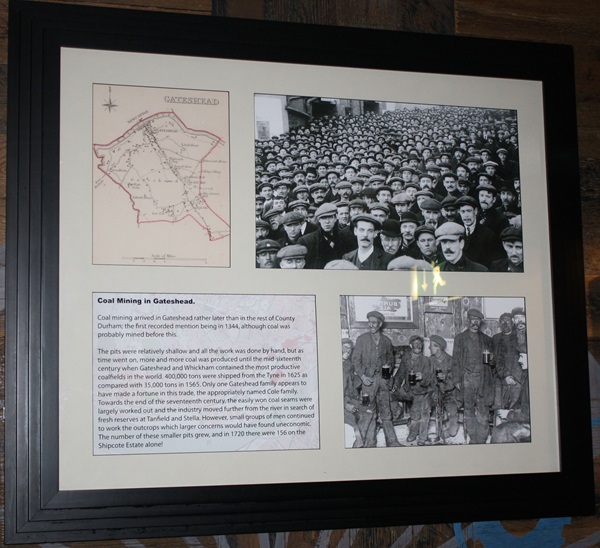

Photographs and text about coal mining in Gateshead

The text reads: Coal mining arrived in Gateshead rather later than in the rest of County Durham, the first recorded mention being in 1344, although coal was probably mined before this.

The pits were relatively shallow, and all the work was done by hand, but as time went on, more and more coal was produced until the mid-16th century when Gateshead and Whickham contained the most productive coalfields in the world. 400,000 tons were shipped from the Tyne in 1625 as compared with 35,000 tons in 1565. Only one Gateshead family appears to have made a fortune in this trade, the appropriately named Cole family. Towards the end of the 17th century the easily won coal seams were largely worked out, and the industry moved further from the river in search of fresh reserves at Tanfield and Stella. However, small groups of men continued to work the outcrops which larger concerns would have found uneconomic. The number of these smaller pits grew, and in 1720 there were 156 on the Shipcote Estate alone!

An illustration entitled The Street Pit Team Colliery, drawn by JH Hair and etched by J Brown

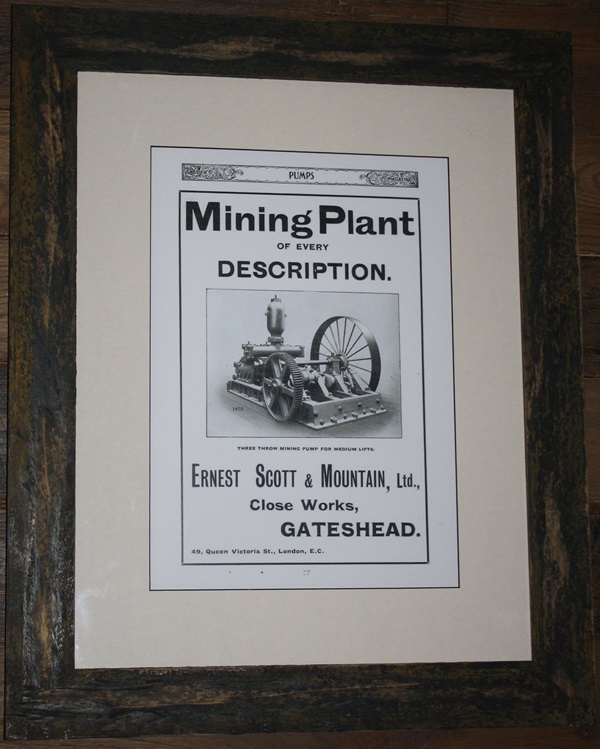

A poster advertising Ernest Scott & Mountain Ltd

This company specialised in mining machinery.

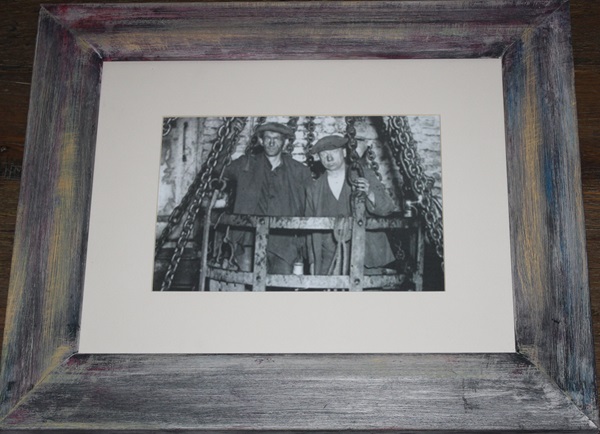

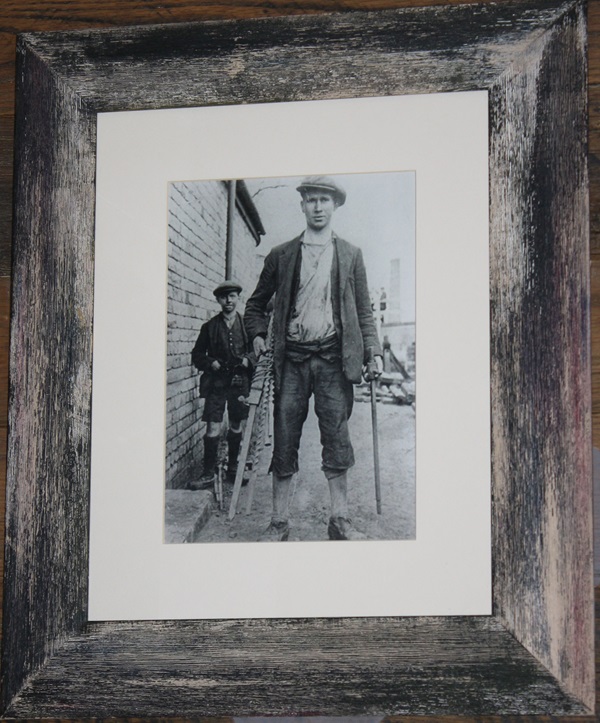

Photographs of coal miners

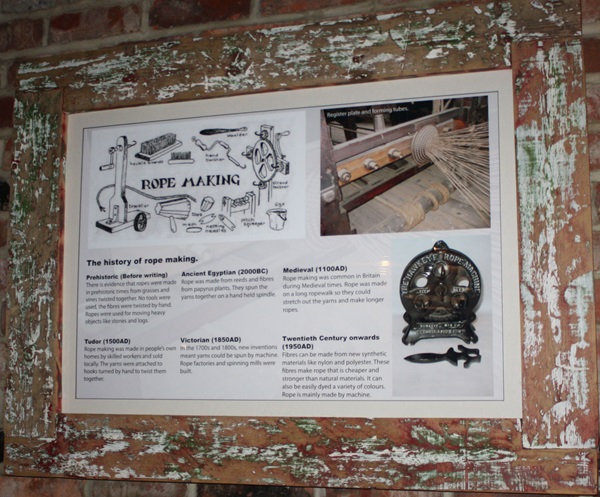

Photographs and text about the history of rope-making

The text reads: Prehistoric (Before writing)

There is evidence that ropes were made in prehistoric times from grasses and vines twisted together. No tools were used; the fibres were twisted by hand. Ropes were used for moving heavy objects like stones and logs.

Ancient Egyptian (2000 BC)

Rope was made from reeds and fibres from papyrus plants. They spun the yarns together on a hand-held spindle.

Medieval (AD 1100)

Rope making was common in Britain during Medieval times. Rope was made on a long ropewalk so they could stretch out the yarns and make longer ropes.

Tudor (AD 1500)

Rope making was performed in people’s own homes by skilled workers and sold locally. The yarns were attached to hooks turned by hand to twist them together.

Victorian (AD 1850)

In the 1700s and 1800s, new inventions meant yarns could be spun by machine. Rope factories and spinning mills were built.

Twentieth Century onwards (AD 1950)

Fibres can be made from new synthetic materials like nylon and polyester. These fibres make rope that is cheaper and stronger than natural materials. It can also be easily dyed a variety of colours. Rope is mainly made by machine.

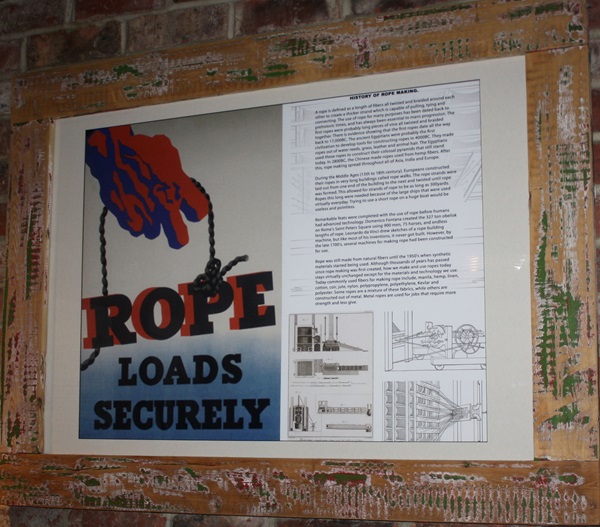

Illustrations, print and text about the history of rope-making

The text reads: A rope is defined as a length of fibres all twisted and braided around each other to create a thicker strand which is capable of pulling, tying and connecting. The use of rope for many purposes has been dated back to prehistoric times, and has always been essential to man’s progression. The first ropes were probably long pieces of vine all twisted and braided together. There is evidence showing that the first ropes date all the way back to 17,000 BC. The Ancient Egyptians were probably the first civilisation to develop tools for constructing ropes, in 4,000 BC. They made ropes out of water reeds, grass, leather and animal hair. The Egyptians used these ropes to construct their colossal pyramids that still stand today. In 2800 BC, the Chinese made ropes using hemp fibres. After this, rope-making spread throughout all of Asia, India and Europe.

During the Middle Ages (13th to 18th century), Europeans constructed their ropes in very long buildings called rope walks. The rope strands were laid out from one end of the building to the next and twisted until rope was formed. This allowed for strands of rope to be as long as 300 yards. Ropes this long were needed because of the large ships that were used virtually every day. Trying to use a short rope on a huge boat would be pointless.

Remarkable feats were completed with the use of rope before humans had advanced technology. Domenico Fontana created the 327-ton obelisk on Rome’s Saint Peter’s Square using 900 men, 75 horses, and endless lengths of rope. Leonardo da Vinci drew sketches of a rope-building machine, but like most of his inventions, it never got built. However, by the late 1700s, several machines for making rope had been constructed for use.

Rope was still made from natural fibres until the 1950s, when synthetic materials started being used. Although thousands of years has passed since rope-making was first created, how we make and use rope today stays virtually unchanged except for the materials and technology we use. Today, commonly used fibres for making rope include, manila, hemp, linen, cotton, coir, jute, nylon, polypropylene, polyethylene, Kevlar and polyester. Some ropes are a mixture of these fabrics, while others are constructed out of metal. Metal ropes are used for jobs that require more strength and less give.

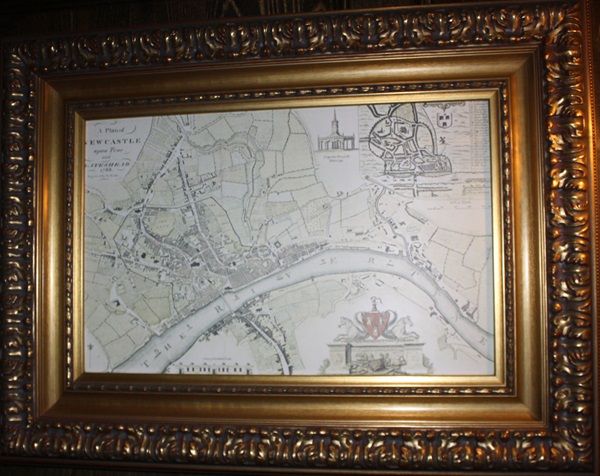

An illustration of a map of Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead, 1788, by Ralph Beilby (1743–1817)

A photograph of James Renforth (7 April 1842 – 23 August 1871)

A famous Tyneside professional oarsman. He became the World Sculling Champion in 1868 and was one of Tyneside’s greatest oarsmen.

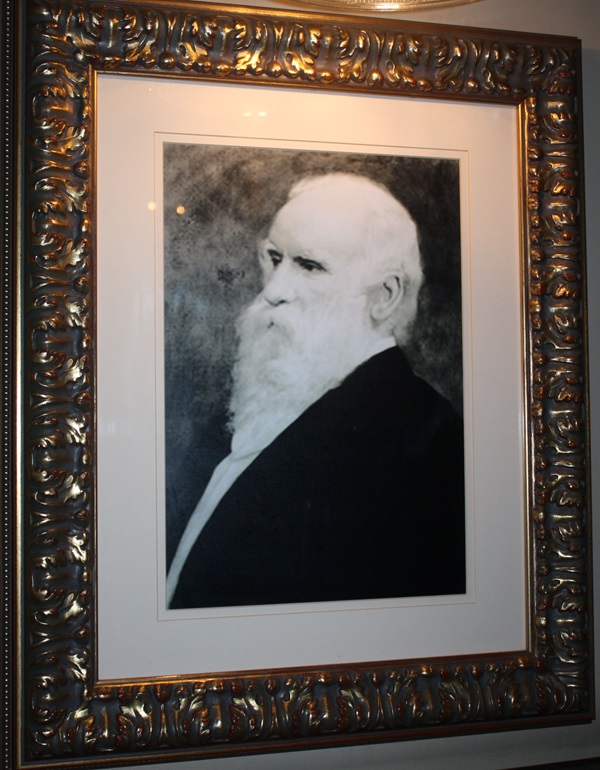

A print of Robert Stirling Newall (1812–89)

Born In Dundee, and Gateshead Mayor in 1867 and 1858. He was a wire rope manufacturer, and his company constructed the rope which towed Cleopatra’s needle up the Thames.

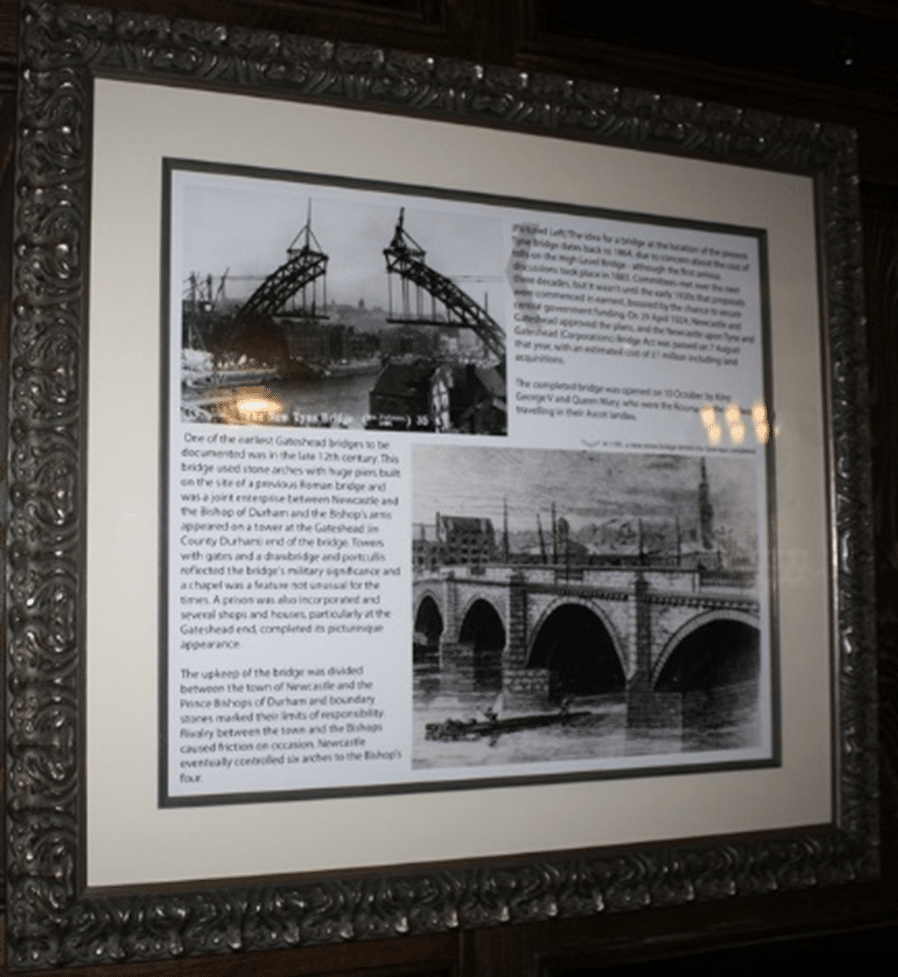

A photograph, illustration and text about The New Tyne Bridge

The text reads: One of the earliest Gateshead bridges to be documented was in the late 12th century. This bridge used stone arches with huge piers built on the site of a previous Roman bridge and was a joint enterprise between Newcastle and the Bishop of Durham, and the Bishop’s arms appeared on a tower at the Gateshead (in County Durham) end of the bridge. Towers with gates and a drawbridge and portcullis reflected the bridge’s military significance and a chapel was a feature not unusual for the times. A prison was also incorporated, and several shops and houses, particularly at the Gateshead end, completed its picturesque appearance.

The upkeep of the bridge was divided between the town of Newcastle and the Prince Bishops of Durham, and boundary stones marked their limits of responsibility. Rivalry between the town and the Bishops caused friction on occasion. Newcastle eventually controlled six arches to the Bishops’ four.

(Pictured left) The idea for a bridge at the location of the present Tyne Bridge dates back to 1864, due to concern about the cost of tolls on the High Level Bridge – although the first serious discussions took place in 1883. Committees met over the next three decades, but it wasn’t until the early 1920s that proposals were commenced in earnest, boosted by the chance to secure central-government funding. On 29 April 1924, Newcastle and Gateshead approved the plans, and the Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead (Corporations) Bridge Act was passed on 7 August that year, with an estimated cost of £1 million including land acquisitions.

The completed bridge was opened on 10 October by King George V and Queen Mary, who were the first to use the roadway, travelling in their Ascot Landau.

An oil painting entitled Angel Over Here, by local artist Allan White

The text reads: Oil on canvas painted by local artist Allan White. Allan was born in Gateshead and has lived and worked in the North East most of his life. He attended university at Nottingham and is a member of the Gateshead Art Society at the Shipley Art Gallery.

An acrylic painting entitled Quayside from the Free Trade, by local artist Emma Holliday

Emma is currently living and working in the North East. Originally from the South, she has lived locally for over 20 years, working with acrylic and oil and can often be found working outside in all weathers.

Commissioned by J D Wetherspoon for The Tilley Stone, Gateshead

External photograph of the building – main entrance